Wildlife corridors are crucial natural pathways that allow animals to move between different habitats for migration, breeding, and accessing food and water sources. These corridors are essential in maintaining ecological balance, genetic diversity, and species survival. Without them, animals can become isolated, leading to inbreeding, resource depletion, and increased human-wildlife conflict.

What are Wildlife Corridors?

Wildlife corridors are designated routes or natural pathways that allow animals to move between different habitats, often crossing human-made barriers like roads or settlements. These corridors are critical in maintaining the ecological balance by enabling the free movement of species for migration, reproduction, and feeding. In the context of the Masai Mara, wildlife corridors connect protected areas, conservancies, and dispersal zones across Kenya’s expansive grasslands.

As human development continues to encroach on wildlife habitats, conserving and protecting these corridors has become increasingly critical. Conservancies play a key role in safeguarding these paths by ensuring that land remains open and accessible to animals, free from obstructions like fences, roads, or settlements. One notable example is the Nashulai Maasai Conservancy, which has taken significant steps to restore and protect a crucial wildlife corridor in the Masai Mara ecosystem.

The Importance of Conservancies for Wildlife Corridors

Conservancies are privately or community-managed areas aimed at preserving natural habitats while benefiting local populations through sustainable practices such as eco-tourism, community-driven conservation, and traditional land use methods. These areas often serve as critical buffers between national parks and other protected areas, allowing wildlife to move freely and safely between regions.

The role of conservancies in creating and protecting wildlife corridors is multi-faceted:

One compelling example of the importance of corridors comes from data collected by Save the Elephant, which shows that more than 60% of Africa’s elephants migrate out of protected areas. Without accessible corridors, these elephants would be forced into isolated pockets, leading to resource depletion and increased human-wildlife conflict as they search for food and water in human-populated areas. Additionally, restricted movement limits genetic diversity, which is crucial for the health and resilience of elephant populations.

- Protection of Habitat: Conservancies ensure that land remains undeveloped and free from urban sprawl, roads, and fences that disrupt wildlife movement.

- Restoration of Degraded Land: Many conservancies actively restore degraded habitats, rehabilitating areas that had been compromised by overgrazing, agriculture, or infrastructure development.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict Mitigation: By creating spaces where wildlife can move freely without coming into direct conflict with humans, conservancies reduce instances of crop-raiding, livestock predation, and other negative interactions between people and animals.

- Community Involvement: Conservancies often involve local communities in conservation efforts, ensuring that both wildlife and humans benefit. These initiatives can include job creation, sustainable agriculture, eco-tourism, and education programs that raise awareness about the importance of wildlife corridors.

Case Study: Nashulai Maasai Conservancy

Nashulai Maasai Conservancy, recognized by the UNDP’s Equator Initiative, is an exemplary case of how conservancies can create and protect vital wildlife corridors while benefiting local communities.

Formation and Goals

In 2016, five villages of around 3,000 people came together to form the Nashulai Maasai Conservancy, the first of its kind in the Mara. Faced with environmental degradation and the threat of losing their ancestral land to outsiders, the Maasai community decided to take action. They adopted traditional rotational grazing methods, which are more sustainable and environmentally friendly. In addition, they removed all fences, which had fragmented the landscape, and reopened a critical corridor used by wildlife during the Great Migration.

Restoration of the Land and Biodiversity

Before the conservancy was established, the land had been severely degraded due to overgrazing, fencing, and other unsustainable land-use practices. In just four years, the Nashulai Maasai Conservancy has managed to nearly restore the land to its original state. The conservancy now supports a wide variety of wildlife, including:

- Elephant birthing grounds: These safe, open spaces are essential for elephant populations, providing them with undisturbed areas to give birth and raise their young.

- Bird sanctuary: Nashulai has become home to a variety of bird species, some of which are rare or endangered. The reforestation and protection of wetlands within the conservancy have created ideal habitats for these birds.

- Giraffe and wild dog populations: The conservancy now boasts some of the largest populations of giraffes and wild dogs in the Mara. These species rely on vast, open spaces to thrive, which Nashulai has successfully provided through its conservation efforts.

Protecting a Great Migration Corridor

One of the most significant achievements of Nashulai has been the reopening of a critical wildlife corridor that is part of the Great Migration route. This corridor allows thousands of wildebeest, zebras, and other animals to pass through the area as they migrate between the Masai Mara and the Serengeti in search of food and water. By removing fences and restoring the land, Nashulai has ensured that this natural migration can continue without human interference, thus supporting one of the world’s most important wildlife events.

Community-Led Conservation

A key feature of the Nashulai Maasai Conservancy is its community-driven approach. The Maasai people, who have long lived in harmony with the land and wildlife, are at the forefront of conservation efforts. By employing sustainable practices like rotational grazing and eco-tourism, the conservancy has created jobs and reduced poverty while protecting the environment.

Eco-tourism has become a significant source of income for the conservancy. Tourists visit Nashulai to experience traditional Maasai culture, see the abundant wildlife, and participate in conservation activities. The revenue generated from eco-tourism is reinvested into conservation projects and community development initiatives, ensuring a sustainable future for both people and wildlife.

Wildlife Corridors and Human-Wildlife Conflict

One of the main challenges facing wildlife corridors is human-wildlife conflict, particularly in areas where communities live in close proximity to migratory paths. In Nashulai, for example, elephants, lions, and wildebeest move through areas that are also used for grazing cattle and farming crops. This can lead to conflict when animals damage property or threaten livestock.

The Nashulai Conservancy has implemented several strategies to mitigate these conflicts, including:

Eco-tourism and job creation: By providing alternative sources of income, such as jobs in eco-tourism, the conservancy has reduced the community’s reliance on farming and livestock, which in turn reduces human-wildlife conflict.

Building community awareness: Education programs help local communities understand the importance of wildlife corridors and how protecting these paths benefits both wildlife and people.

Traditional land-use practices: By reintroducing rotational grazing, the conservancy has reduced competition between livestock and wildlife for resources, thereby decreasing instances of conflict.

Importance of Wildlife Corridors in Masai Mara

The Masai Mara is one of the world’s most renowned wildlife reserves, home to the iconic annual Great Migration, where millions of wildebeest, zebras, and other herbivores move across the plains. The wildlife corridors in the region are essential for:

- Migration: Allowing species to follow traditional migratory routes, particularly for elephants, wildebeest, and zebra.

- Genetic Diversity: Facilitating animal movement helps prevent inbreeding by connecting isolated populations.

- Adaptation to Climate and Environmental Changes: With shifting seasons and food sources, corridors allow animals to move between regions for resources like water and grazing land.

- Reducing Human-Wildlife Conflict: By providing designated paths for animal movement, corridors reduce the chances of wildlife straying into human settlements, reducing crop damage and confrontations.

Key Wildlife Corridors in the Masai Mara Ecosystem

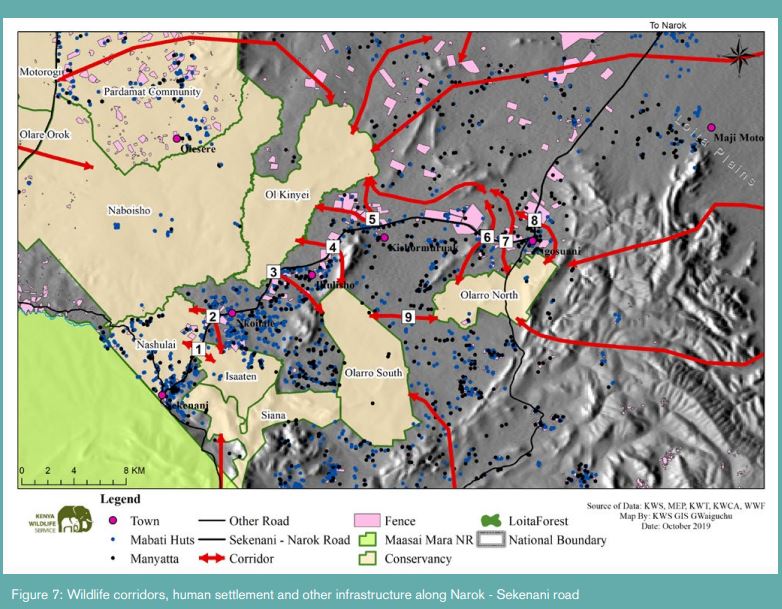

In the Masai Mara ecosystem, there are a total of 18 critical wildlife corridors, nine of which cross the upgraded Sekenani-Narok C13 road. The upgrade of this road to tarmac has exacerbated emerging threats from human infrastructure development, which is rapidly accelerating along the road. These corridors are essential for the movement of wildlife between key conservancies, grazing areas, and salt licks. However, with increasing human settlements, fencing, and the expansion of road networks, the connectivity of these wildlife pathways is at risk.

Among the identified corridors, some of the most important include the Nashulai-Isateen, Ol Kinyei-Olarro, and the Olare Orok-Pardamat routes. These corridors serve as vital links for species like elephants and wildebeest, facilitating their seasonal migration and ensuring genetic diversity, while also maintaining access to critical resources. Safeguarding these routes is crucial for the conservation of the Masai Mara’s biodiversity and the sustainable coexistence between wildlife and local communities.

Below is a list of all the wildlife corridors in Masai Mara Ecosystem.

- Corridor 1: Nashulai and Isateen Conservancies

- Corridor 2: Nashulai and Isateen via community lands

- Corridor 3: Ol Kinyei to Olarro Conservancies

- Corridor 4: Ol Kinyei to Olarro South Conservancies

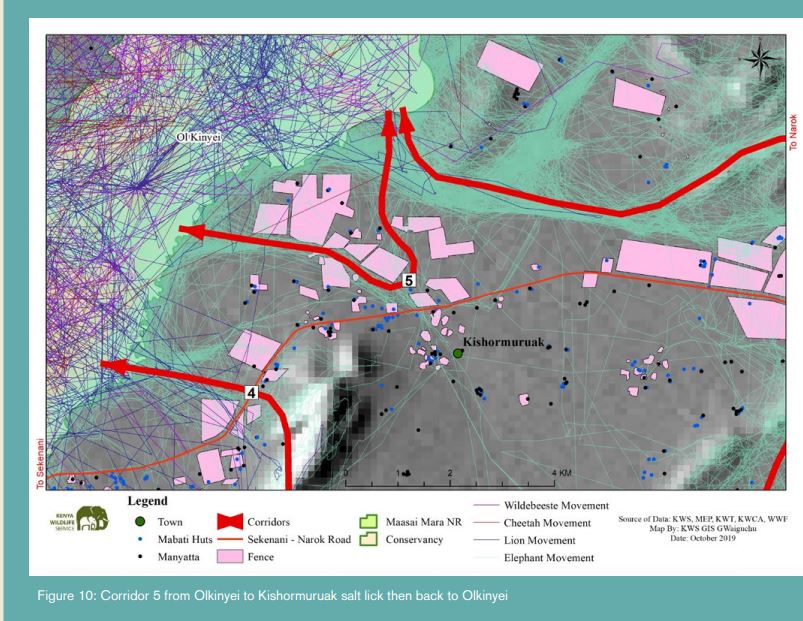

- Corridor 5: Ol Kinyei to Kishormuruak salt lick

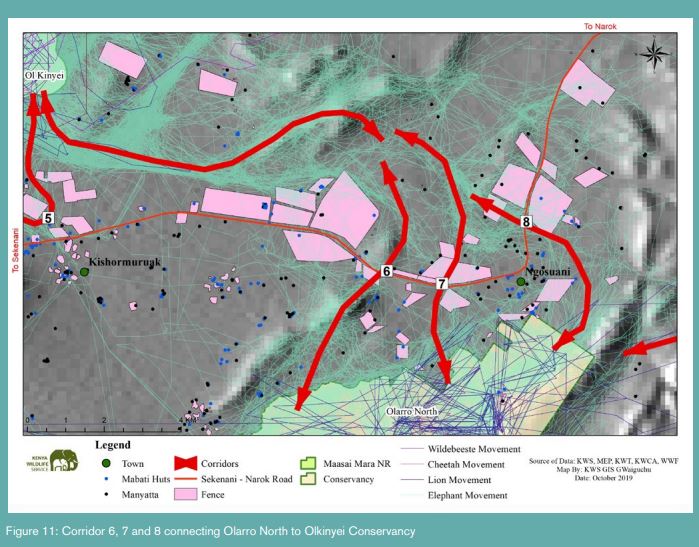

- Corridor 6: Olarro North to Ngosuani South (southern path)

- Corridor 7: Olarro North to Ngosuani South (central path)

- Corridor 8: Olarro North to Ngosuani (northern path)

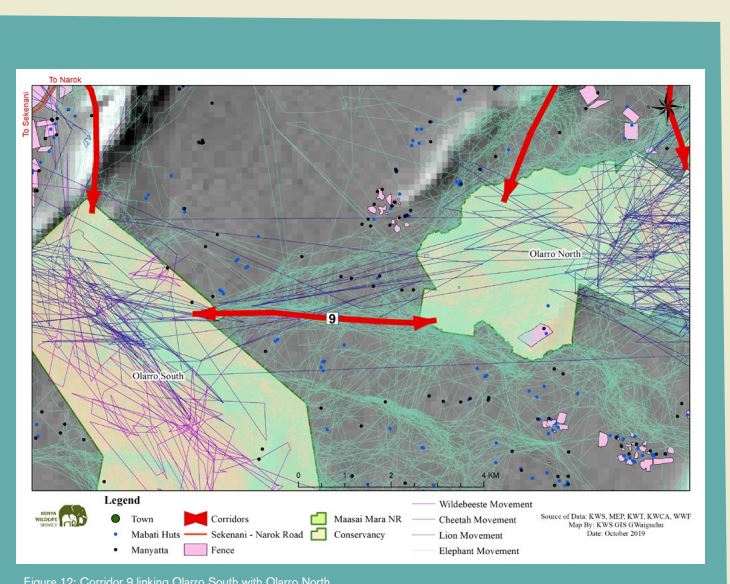

- Corridor 9: Olarro South and North Conservancies

- Corridor 10: Olare Orok to Pardamat Community Conservancy

- Corridor 11: Ol Kinyei Conservancy to Mara Naboisho Conservancy

- Corridor 12: Naboisho to Nashulai Conservancy

- Corridor 13: Naboisho to Olare Orok Conservancy

- Corridor 14: Olarro North to Loita Hills

- Corridor 15: Mara Naboisho Conservancy to Pardamat Community Conservancy

- Corridor 16: Olarro Conservancy to Loita Forest

- Corridor 17: Olarro North to Loita Plains

- Corridor 18: Siana Conservancy to Loita Hills

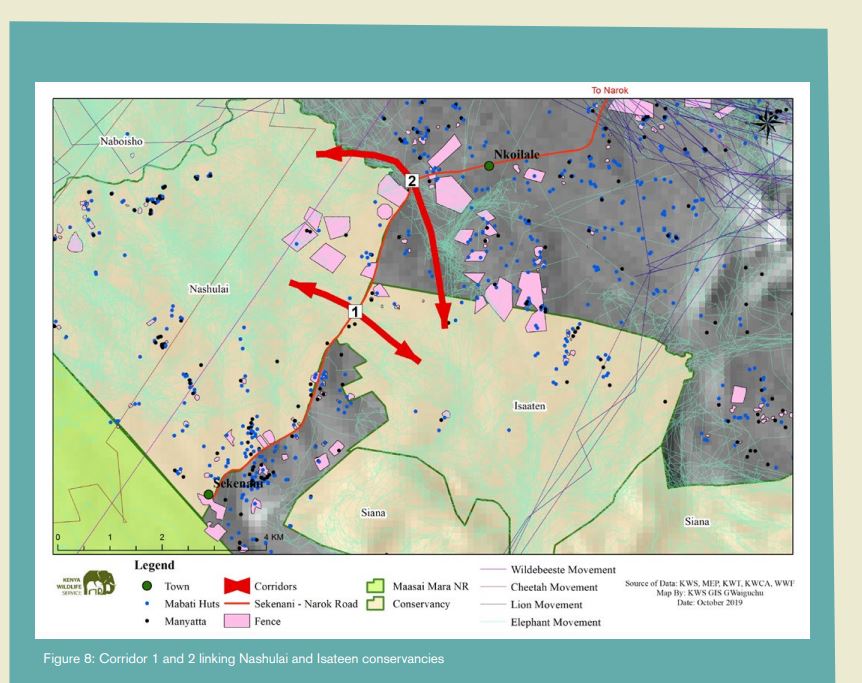

1. Nashulai and Isateen Conservancies Corridor

The corridor connects the Nashulai and Isateen conservancies, separated by the upgraded Narok-Sekenani Tarmac Road. Nashulai joins Naboisho to the west, securing a previously lost corridor. This passage allows elephants and other animals to move between Naboisho, Siana, and Olarro conservancies. While no physical barriers block the corridor yet, the road and emerging settlements are potential risks to wildlife movement.

2. Talek River Corridor

This corridor runs along the Talek River, connecting the northern side of Nashulai Conservancy with other conservancies. The path loops across community lands and crosses the Narok-Sekenani road via a bridge. While critical for the movement of elephants, lions, and wildebeest, the corridor faces challenges such as fences, permanent structures, and human settlements.

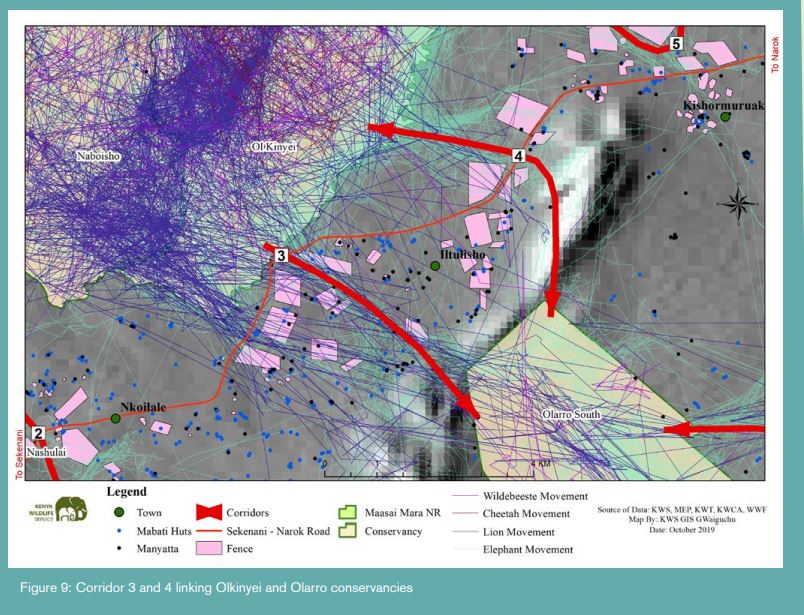

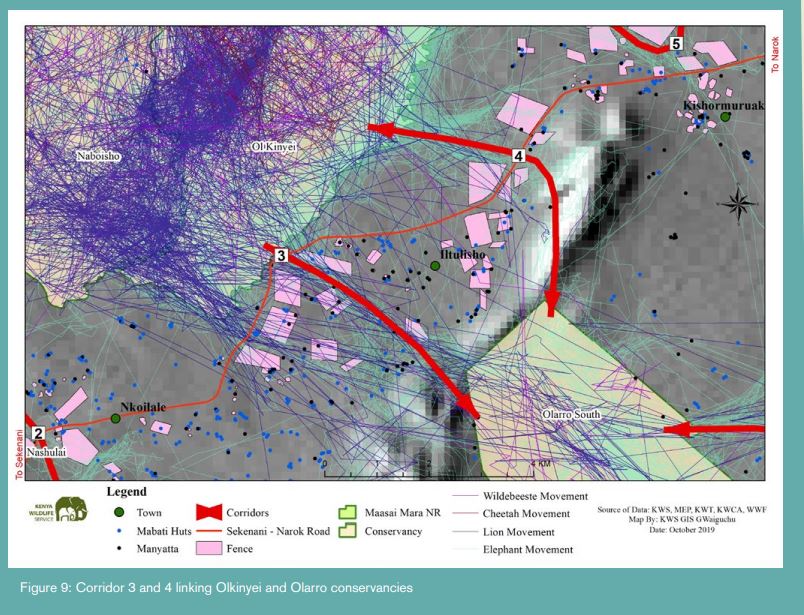

3. Ol Kinyei to Olarro Conservancy Corridor

A key corridor connecting Mara Naboisho and Ol Kinyei Conservancies with Olarro Conservancy. Elephants frequently use this path, crossing the Narok-Sekenani road. Fencing and private land ownership are barriers along the route, although carnivores can pass under bridges and through fences. This corridor is crucial in connecting western conservancies to Siana, Olarro, and the Loita Hills.

4. Olkinyei and Olarro South Corridor

This corridor passes through the hills and community settlements, connecting Olkinyei and Olarro South conservancies. The Narok-Sekenani tarmac road and fences are significant obstacles, but the corridor remains essential for elephant movement between conservancies.

5. Olkinyei to Kishormuruak Salt Lick Corridor

This corridor follows a riverine habitat and is primarily used by elephants moving to the salt licks. However, human settlement has blocked the route entirely near Kishormuruak, forcing elephants to return to Olkinyei Conservancy after reaching the salt licks. The corridor spans approximately 7.7 kilometers but faces growing threats from fences and settlements.

6, 7, and 8. Olarro North to Ol Kinyei Corridor

Three primary paths connect Olarro North Conservancy with Ol Kinyei, passing through areas critical for elephants. The routes merge near Ngosuani center, which is rapidly being settled, adding fences and other barriers to the already challenging path. These corridors also connect with the Olare Lemuny salt licks, a key area for elephant dispersal.

9. Olarro South and North Corridor

This recently extended corridor links Olarro South and North conservancies, creating a passageway for elephants between the Mara population and Loita Hills. However, fencing and settlement are growing issues, requiring urgent conservation efforts to protect the connectivity of this route.

Wildlife Movement Patterns and the Role of Corridors

Elephant Migration Routes

Elephants are perhaps the most frequent users of these corridors, with significant paths crossing the Narok-Sekenani road. Elephants use these routes during both day and night, moving between conservancies in search of water, grazing lands, and salt licks. The corridors facilitate elephant movement across conservancies such as Naboisho, Olkinyei, and Olarro, allowing them to follow seasonal changes and maintain healthy population dynamics.

Wildebeest and Cheetah Movement

The Great Migration of wildebeest also relies on these corridors, particularly the paths that connect the Mara Reserve with conservancies like Nashulai, Olkinyei, and Siana. During migration, wildebeest move in large numbers through these corridors, supported by cheetah movement that follows prey across the plains. Barriers such as roads and fences pose significant challenges to their free movement, particularly in community land areas.

Challenges Facing Wildlife Corridors in Masai Mara

While wildlife corridors are vital to the health of the Masai Mara ecosystem, they face several threats:

- Infrastructure Development: Roads like the Narok-Sekenani tarmac road create physical barriers that hinder wildlife movement, particularly for larger animals like elephants and wildebeest. Settlements along these roads exacerbate the issue.

- Fencing: With increasing privatization and development of land, fences block traditional migration routes. In some cases, these barriers are electrified, making it impossible for wildlife to pass through safely.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict: As wildlife movement overlaps with human settlements, conflicts arise. Crops are damaged, livestock attacked, and human injuries or fatalities occur when wildlife strays into populated areas.

- Settlement and Land Use Changes: Rapid population growth in areas surrounding the conservancies has led to increased settlement, further encroaching on wildlife corridors and reducing the land available for animal movement.

Conservation Initiatives and Future of Wildlife Corridors

Efforts to protect and maintain wildlife corridors in the Masai Mara are crucial to preserving the delicate balance of its ecosystem. Conservation organizations, along with local communities, are working on several fronts to ensure these paths remain viable:

- Community Conservation: Engaging local communities in conservancy efforts and wildlife management helps reduce human-wildlife conflict and allows for shared use of land.

- Fencing Alternatives: Where possible, efforts are made to implement wildlife-friendly fencing that allows certain species to pass while preventing livestock from straying.

- Protected Corridor Zones: Designating official protected wildlife corridors ensures that development and infrastructure projects are restricted in these areas.

What You and the Locals Do to Help?

- Respect Fences: When visiting or living near wildlife corridors, it’s important to minimize fencing or use wildlife-friendly fencing solutions.

- Support Conservancies: Visiting and supporting conservancies like Nashulai helps fund the continued protection of wildlife corridors.

- Drive Carefully: If you’re driving on roads like the Sekenani-Narok road, be mindful of wildlife crossings, especially at night.

- Spread Awareness: The more people understand the importance of wildlife corridors, the more action can be taken to protect them.

Conclusion

Wildlife corridors are the lifeline of the Masai Mara, allowing animals to thrive by maintaining their natural movement patterns. With rising human activity and infrastructural barriers, it is essential to focus on the preservation of these corridors for the survival of iconic species like elephants, wildebeest, and lions. Conservation efforts need to balance the needs of both wildlife and local communities to ensure the sustainability of these vital routes.

Through careful management and protection, Masai Mara’s wildlife corridors can continue to support the incredible biodiversity that makes this region one of the world’s most important ecosystems.

Related: