Where did the word “safari” originate, and what does it mean? How do modern safaris differ from historical expeditions in Africa? How has the meaning of the word safari changed over timeWhich destinations offer the best safari experiences today? These questions capture the curiosity of both nature enthusiasts and first-time adventurers who are keen to learn more about this unique form of travel from safari fans and experts alike. In this exhaustive guide to safari, its meaning and origin, we’ll cover all that including details of its evolution over time.

Here’s the meaning of Safari

The origin of the word safari is closely tied to the East African coast, specifically the regions that now comprise Kenya and Tanzania, where Swahili culture flourished through extensive interactions with Arab traders. These interactions, dating back as early as the 8th century, led to the adoption of many Arabic words into the Swahili language, including safari, which comes from the Arabic term safar, meaning “journey” or “travel.

Originally, the term referred to the long-distance travels undertaken by Arab and African traders across vast landscapes, moving goods like ivory, spices, and gold. These journeys were not just simple trips; they involved traversing harsh and untamed terrains.

The East Africa region became the birthplace of the modern safari as Western explorers and traders began to penetrate Africa’s interior in the 19th century. For them, “safari” came to represent an adventurous expedition, usually aimed at exploration or big-game hunting.

Thus, while the origins of safari lie in the Arabic and Swahili cultures, signifying a functional journey, the word was transformed into a symbol of adventure, leisure, and Western exoticism in Africa. Over time, as conservation replaced hunting, “safari” came to be associated more with wildlife observation, eco-tourism, and the immersive experience of Africa’s wilderness, but its roots in the great historical journeys remain.

Earliest use of the word

The earliest known use of the word safari in English is widely attributed to Richard Francis Burton in 1860, when he introduced the Swahili term in his publication The Lake Regions of Central Africa. Burton, known for his linguistic expertise and extensive travels in East Africa, used the word safari, meaning “journey,” to describe his explorations and journeys through the African wilderness. This marked the formal introduction of the term into English, where it became associated with overland expeditions, particularly in the context of exploration and big-game hunting.

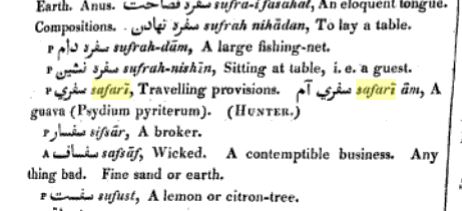

However, a deeper dive into sources like Google Books Ngram Viewer reveals that the word safari appears in English-language publications as early as the 1820s, notably in this Persian-English-Arabic Dictionary from 1829, which suggests the term was in circulation earlier than Burton’s well-documented use.

Richard Burton still takes credit for popularizing it in the West

Despite these earlier occurrences, Burton’s role in popularizing the term cannot be overstated. His travels and writings aligned with the 19th-century European fascination with Africa, helping to cement safari in the lexicon of Western explorers and adventurers.

Burton’s use of safari and the romanticism surrounding his expeditions played a pivotal role in transforming the term into a cultural symbol of adventure. Over time, safari became associated with the grandeur of overland journeys across Africa, particularly for hunting, and later evolved into wildlife observation and eco-tourism. While earlier records of the word exist, Burton’s influence remains significant for shaping the broader Western understanding and subsequent adoption of safari as a key element of African exploration.

Other major figures who contributed to the rise and spread of the word safari

1. Frederick Courteney Selous (1851–1917)

- Contribution: Frederick Courteney Selous was one of the most famous big-game hunters and explorers of his time, and his exploits had a lasting influence on Western ideas of safari. A British-born adventurer, Selous spent over 30 years hunting and exploring in southern Africa, chronicling his experiences in several books, including A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa (1881), which became a foundational text for the genre.

- Impact: Selous’s writings inspired generations of explorers, hunters, and naturalists, and he was celebrated as a heroic figure of imperial adventure. His accounts of dangerous hunts for lions, elephants, and rhinos shaped the Western public’s fascination with the exotic and untamed African wilderness.

- Legacy: Selous became the archetype of the rugged, fearless white hunter, a figure that would dominate safari culture in the 20th century. The Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania, one of Africa’s largest protected areas, is named in his honor, though ironically it stands as a symbol of the conservation movement that came after his era of mass wildlife hunting.

2. Denys Finch Hatton (1887–1931)

- Contribution: An aristocratic British hunter and lover of adventure, Denys Finch Hatton became iconic through his romanticized portrayal in Karen Blixen’s memoir Out of Africa (1937). Finch Hatton’s safaris were less about hunting and more about exploring Africa’s landscapes and experiencing its wildlife in a more respectful manner. He conducted many safaris with British royalty and high-profile figures, introducing them to the African wilderness.

- Impact: Finch Hatton was emblematic of a shift in the early 20th century from purely trophy hunting to a more nuanced engagement with the African landscape. His charm, elegance, and deep love of Africa helped popularize the notion of safari as a luxurious and exotic experience rather than purely a hunting expedition.

- Legacy: Although he was not a prolific writer, Finch Hatton’s influence spread through his association with Karen Blixen and her literary depiction of their relationship, turning him into a symbol of aristocratic adventure. His life and death (in a plane crash in the Kenyan bush) further added to his mythic status.

3. Baron Bror von Blixen-Finecke (1886–1946)

- Contribution: Bror von Blixen, a Swedish baron and the husband of Karen Blixen (author of Out of Africa), was another notable figure who popularized safaris in the early 20th century. A professional hunter and safari guide in Kenya, Bror gained fame for leading safaris for wealthy clients, including European royalty and Hollywood stars.

- Impact: As a charismatic and experienced safari guide, Blixen-Finecke embodied the “great white hunter” persona that fascinated Western society. His clients included famous figures like Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII), and his exploits helped solidify the safari as a prestigious, adventurous endeavor for the Western elite.

- Legacy: Despite his personal flaws, including his reckless lifestyle, Bror von Blixen’s reputation as a skilled safari leader and larger-than-life personality made him one of the enduring figures of safari lore. His life is also intertwined with that of Karen Blixen, whose writings immortalized their time in Africa.

4. Carl Akeley (1864–1926)

- Contribution: Unlike other big-game hunters of his time, Carl Akeley was a pioneering American taxidermist, naturalist, and conservationist whose expeditions to Africa were primarily focused on collecting specimens for scientific study and museum displays. He is best known for his work at the American Museum of Natural History, where his realistic dioramas of African animals (many of which were hunted by Akeley himself) captivated the public’s imagination.

- Impact: Akeley’s safaris and expeditions, including multiple trips to Africa, led to the creation of some of the most famous museum exhibits of African wildlife in the world. His efforts to document, preserve, and display African wildlife for scientific and educational purposes introduced millions of Westerners to the richness of African fauna.

- Legacy: Akeley’s work helped lay the groundwork for modern wildlife conservation, as he eventually advocated for the protection of African animals rather than their destruction. His vision led to the establishment of national parks in Africa, including the Virunga National Park in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, where he worked to protect mountain gorillas.

5. Philip Percival (1886–1966)

- Contribution: Philip Percival was a professional hunter and one of the most famous safari guides of his time. Known for leading safaris for prominent figures such as Ernest Hemingway and Theodore Roosevelt, Percival was deeply respected for his knowledge of African wildlife and his skill as a hunter. His life and career epitomized the glamorous yet dangerous allure of the African safari.

- Impact: Percival’s reputation as a skilled safari leader attracted wealthy and powerful clients, further cementing the image of the safari as an elite adventure. His safaris were considered quintessential African experiences, blending danger, exploration, and wildlife observation.

- Legacy: Percival’s influence extended beyond his clients; he was the inspiration for Hemingway’s character Robert Wilson in The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber. His name became synonymous with the idea of the safari as a rite of passage for Western adventurers in Africa.

6. William Cornwallis Harris (1807–1848)

- Contribution: Although Harris lived in the 19th century, his impact on safari culture continued into the 20th century. As one of the earliest European explorers to engage in big-game hunting in Africa, Harris’s 1836–1837 expedition to southern Africa set a precedent for later safari hunters. His published works, particularly The Wild Sports of Southern Africa (1841), helped introduce the idea of big-game hunting to Victorian audiences.

- Impact: Harris’s combination of exploration, hunting, and scientific observation became a model for future safari expeditions. His detailed descriptions of Africa’s wildlife and his triumphant, often exaggerated, accounts of hunts influenced the ethos of safari that persisted well into the 20th century.

- Legacy: Harris is often considered one of the founding figures of the “great white hunter” narrative. His work continued to be referenced in the early 20th century as the Western fascination with African safaris reached its height.

As the term safari gained traction among scholars, two key figures propelled it into the global spotlight. Ernest Hemingway immortalized safari through his literary works like The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Green Hills of Africa, capturing the allure and thrill of African wildlife expeditions. Meanwhile, Theodore Roosevelt popularized safaris through his highly publicized 1909 hunting expedition, bringing widespread attention to the adventurous and rugged nature of African tours. Both men helped elevate safari from a scholarly term to a symbol of adventure and exploration.

Here is a closer look at contributions by the two;

7. Theodore Roosevelt

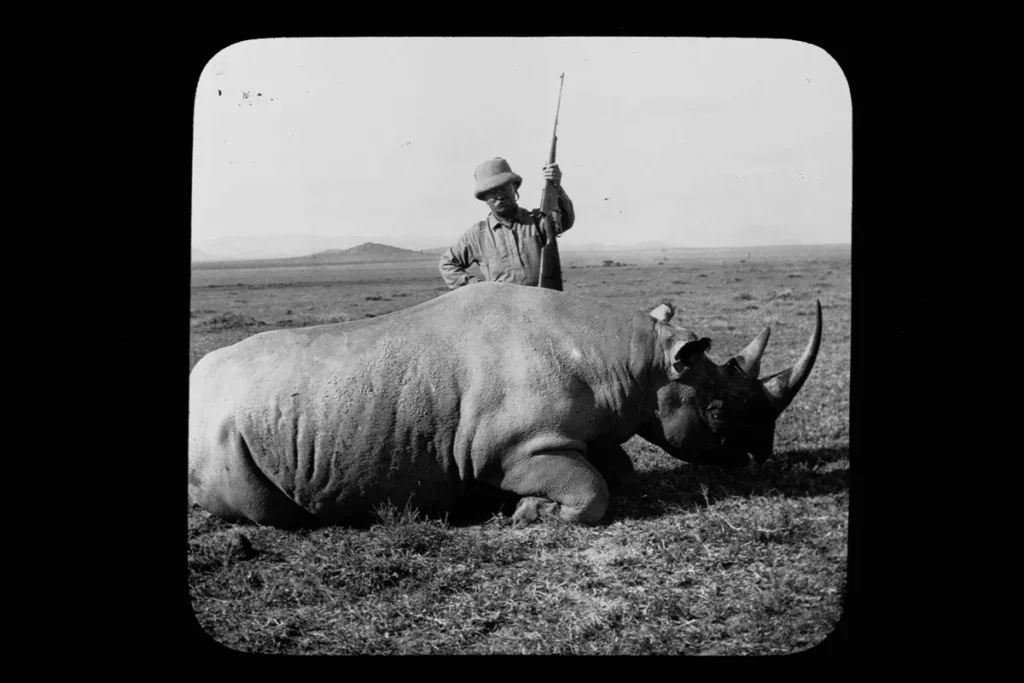

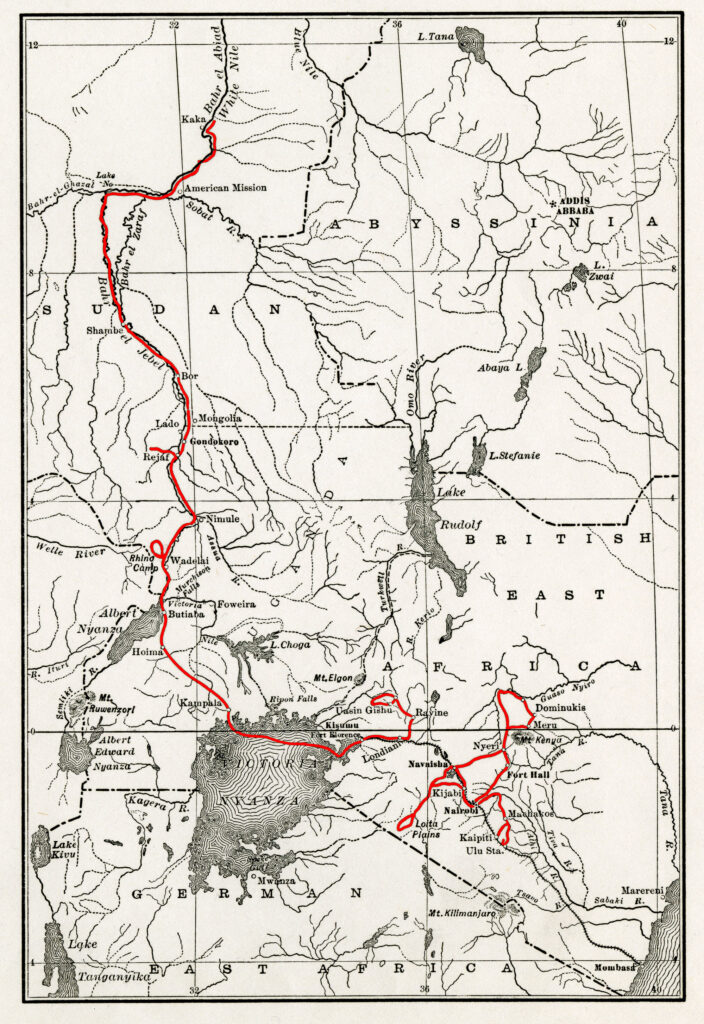

In 1909, shortly after leaving office, Theodore Roosevelt led one of the most famous and controversial African safari expeditions in history. Known as the Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition, it was funded by the Smithsonian Institution to collect specimens for the National Museum of Natural History.

This massive hunting expedition saw Roosevelt and his team gather thousands of animal specimens, making it one of the largest and most debated safaris of its time due to its focus on big-game hunting.

Roosevelt and his team—comprising professional hunters, scientists, and his son, Kermit—spent nearly a year traveling across East and Central Africa, covering regions in modern-day Kenya, Uganda, and the Congo. Their mission was ostensibly scientific: to gather and catalog specimens of Africa’s wildlife. However, the scale of the killings during the trip remains staggering by today’s ethical standards.

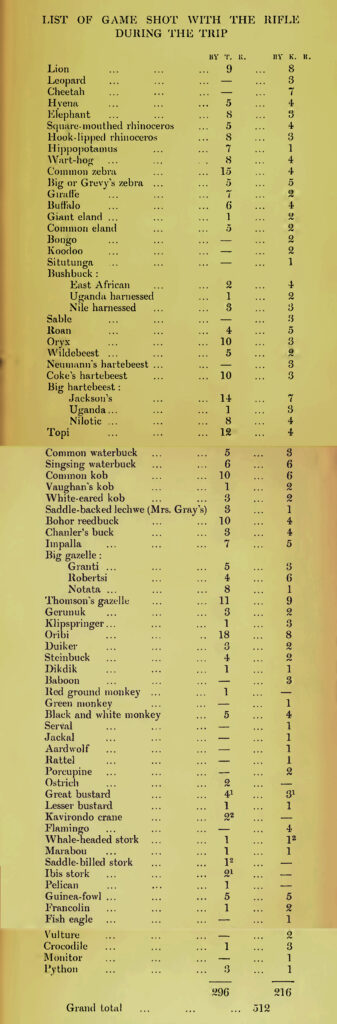

Roosevelt, a passionate naturalist and conservationist in his political life, paradoxically participated in the slaughter of 11,397 animals during this expedition. This figure includes 512 large mammals, among them 17 lions, 19 zebras, 27 gazelle, 11 elephants, 20 rhinos, 9 giraffes, and countless other animals such as buffaloes, hippos, topi, and antelope. The animals were captured or killed not only for museum displays but also for the thrill of the hunt, a practice that was regarded at the time as a demonstration of manliness and prowess.

ere’s the table recreated in a format you can easily copy and paste:

| Animal | Animals Killed by Theodore Roosevelt | Animals Killed by Kermit Roosevelt | Total Animals Killed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lion | 9 | 8 | 17 |

| Leopard | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Cheetah | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Hyena | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Elephant | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Square-mouthed rhinoceros | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Hook-lipped rhinoceros | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Hippopotamus | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Wart-hog | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Common zebra | 15 | 15 | 30 |

| Big or Grevy’s zebra | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Giraffe | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Buffalo | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Giant eland | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Common eland | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Situtunga | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Bushbuck (East African) | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Bushbuck (Uganda harnessed) | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Bushbuck (Nile harnessed) | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Sable | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Roan | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Oryx | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| Wildebeest | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Neumann’s hartebeest | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Coke’s hartebeest | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| Big hartebeest (Jackson’s) | 14 | 7 | 21 |

| Big hartebeest (Uganda) | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Big hartebeest (Nilotic) | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Topi | 12 | 4 | 16 |

| Common waterbuck | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Singsing waterbuck | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Common kob | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| Vaughan’s kob | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| White-eared kob | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Saddle-backed lechwe (Mrs. Gray’s) | 10 | 4 | 14 |

| Bohor reedbuck | 10 | 4 | 14 |

| Chanler’s buck | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Impalla | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| Big gazelle (Granti) | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Big gazelle (Robertsi) | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Big gazelle (Notata) | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Thomson’s gazelle | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Gerunuk | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Klipspringer | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Oribi | 18 | 8 | 26 |

| Duiker | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Steinbuck | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Dikdik | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Baboon | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Red ground monkey | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Green monkey | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Black and white monkey | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Serval | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Jackal | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Aardwolf | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rattel | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Porcupine | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Ostrich | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Great bustard | 41 | 31 | 72 |

| Lesser bustard | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Kavirondo crane | 22 | 1 | 23 |

| Flamingo | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Whale-headed stork | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Marabou | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Saddle-billed stork | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Ibis stork | 21 | 0 | 21 |

| Pelican | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Guinea-fowl | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Francolin | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Fish eagle | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Vulture | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Crocodile | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Monitor | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Python | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 296 | 216 | 512 |

Roosevelt was meticulous in documenting his exploits. His writings, notably in African Game Trails (1910), provide vivid descriptions of the hunts, the landscapes, and the African cultures he encountered. These accounts helped popularize safari hunting in Western culture, cementing it as a symbol of adventure and exploration.

I got a copy of the book and read through it. While it doesn’t explicitly mention reaching the modern-day Masai Mara, they did traverse the larger Mara region via the Loita Hills. Notably, Kermit killed a lion during this leg of the journey, as detailed on pages 194-195 of African Game Trails. In page 196, Kermit kills a Cheetah managed to get a picture of it. Poor Cheetah! Cheetah numbers in the Masai Mara have dwindled to fewer than 30—perhaps we could trace the origins of this decline back to Roosevelt, who arguably set the precedent for big-game hunting in the region. Gazelle(page 200), and warthog(page 198) are other animals that got shot during the Mara region leg of the safari.

The early introduction of safaris in the Masai Mara by explorers and hunters like Roosevelt marked a dark period of widespread game hunting. However, today, the Masai Mara stands as a global model for conservation, thanks to the innovative conservancy model where local Maasai communities lease land for wildlife protection in exchange for tourism revenue. This approach showcases how once-marginalized communities now lead in environmental protection, setting an inspiring example for the world.

Visitors coming for wildlife safaris in Masai Mara now contribute significantly through entry fees, which fund land conservation, ensuring animals roam freely and safeguarding key migration corridors. The collaboration between Maasai communities, conservation organizations, and tourists has created a sustainable balance between wildlife preservation and community development, securing a future for both essentially replacing game hunting safaris with sustainable game viewing/drive safaris.

Surprisingly, after their adventures in the Loita Hills, Roosevelt made his way to Sotik, a town near my home in Bomet. Let me not keep on discussing the book.

The book is available for free on Biodiversitylibrary.org here.

The Library of Congress has video footage of the 1909 trip.

It’s fascinating to see how the dancing performed for Roosevelt in the video closely resembles the modern-day Maasai dances that are still showcased to tourists during village tours. Even today, the Maasai continue to sing and perform these traditional dances, offering visitors a glimpse into their enduring culture.

Roosevelt’s expedition, when viewed through a modern lens, represents a particularly dark chapter in the history of big-game hunting. The sheer number of animals killed reflects a disturbing disregard for wildlife preservation. Though Roosevelt saw himself as a conservationist—he is credited with helping to establish the U.S. National Park System doubling number of national parks during his presidency—his actions in Africa speak to a deeper cultural and ethical contradiction. At that time, hunting was seen not as a threat to species survival, but as a noble pursuit and a way to advance scientific knowledge.

The slaughter of thousands of animals was justified under the guise of natural history collection, but the truth remains that this safari, like many others of the era, was fundamentally about imperial conquest and domination over nature. African wildlife was treated as a resource to be exploited for trophies, museum exhibits, and personal glory. The number of animals killed in Roosevelt’s expedition devastated local populations, though it was seen as part of the Western drive to “civilize” and understand the natural world.

Roosevelt’s actions also played into the broader imperialist attitudes of the time, where African land and wildlife were viewed as existing for the taking by Western explorers, often at the expense of the local environment and indigenous peoples. Safaris, particularly big-game hunts like Roosevelt’s, were part of a colonial mindset that saw Africa as a vast, untapped frontier where rich Westerners could assert dominance over nature and wildlife.

This history is starkly at odds with modern conservation ethics, where the focus is on protecting endangered species and preserving biodiversity. Today, many of the animals that Roosevelt hunted in such large numbers—like rhinos and elephants—are endangered, and big-game hunting is increasingly criticized as an unethical and outdated practice.

Theodore Roosevelt’s African safari thus serves as a glaring example of how Western explorers and colonial powers exploited African wildlife on an industrial scale, often under the pretense of scientific or exploratory ventures. It stands as a sobering reminder of the destructive impact that unchecked human activity can have on the natural world and the often conflicting legacy of those who, like Roosevelt, claimed to champion conservation while simultaneously contributing to the decimation of wildlife.

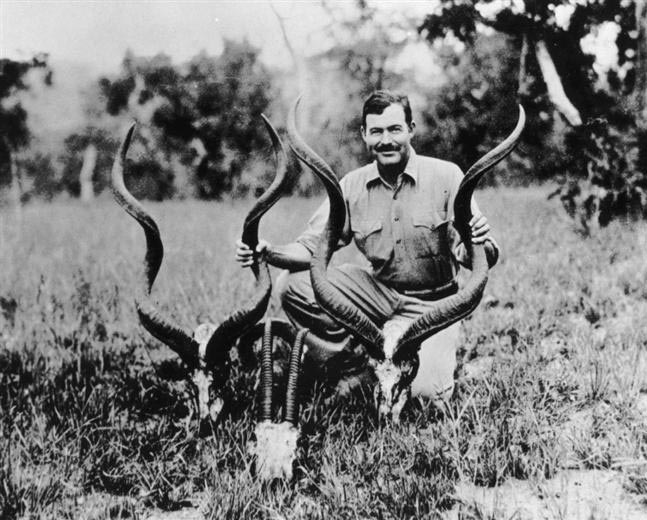

8. Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway had a profound influence on the modern concept of safari through both his adventures and his writing. A passionate outdoorsman, Hemingway first traveled to Africa in 1933 on a big-game hunting safari. This trip became the inspiration for some of his most famous works, including Green Hills of Africa (1935), The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1936), and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber (1936).

Hemingway’s first African safari was a three-month journey through Kenya and Tanzania (then Tanganyika). He was captivated by the raw beauty of the landscape and the thrill of hunting large game, including lions, leopards, and buffaloes. The expedition also served as a period of personal exploration and reflection, which heavily influenced his writing style, making his safari exploits more than just hunting trips—they were existential journeys.

His experiences in Africa portrayed a deeply romantic and rugged view of the continent. Hemingway was known for his hunting prowess, often going on dangerous hunts that pushed him to his physical limits. He survived several close calls, including a severe plane crash in Uganda during his second African trip in 1954, which left him with significant injuries but also heightened his legendary status.

Hemingway’s depiction of safari life—its dangers, excitement, and the sheer vastness of the African wilderness—helped romanticize the concept of safari for Western audiences. His writing contributed to the notion of Africa as an untamed frontier, where adventure and personal conquest awaited. Even today, his legacy is felt in the world of safari, where the image of the rugged explorer living on the edge continues to attract thrill-seekers and travelers.

Beyond hunting, Hemingway’s deep admiration for African culture and landscapes permeated his work, blending the thrilling aspects of safari with a broader narrative about the human condition, mortality, and the relentless pursuit of meaning. His adventures helped cement the idea of safari not just as a hunting excursion, but as a symbolic journey of discovery.

How early 20th Century Safaris Involved Animals Killing in the name of Conservation;

In the early 20th century, safaris involving the large-scale killing of animals were paradoxically tied to conservation efforts, due to the prevailing attitudes and understanding of wildlife management at the time. Several reasons explain this contradiction:

- Scientific Exploration and Specimen Collection: Expeditions like Theodore Roosevelt’s Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition in 1909 aimed to collect specimens for scientific research and museums. The focus was on cataloging and understanding African wildlife, which was relatively unknown to Western scientists. Specimens were needed for study, museum displays, and documentation, which required killing the animals.

- Conservation Through “Culling”: The belief at the time was that killing large numbers of animals for scientific purposes or big-game trophies helped regulate and maintain healthy wildlife populations. This idea stemmed from early conservationist thinking that controlled hunting could prevent overpopulation of certain species and ensure that natural resources were managed sustainably.

- Western Views of Wilderness: Early conservationists, many of whom were avid hunters like Roosevelt, believed that hunting was a way to connect with and manage the wilderness. Wildlife was seen as an abundant resource that needed to be harvested wisely, and trophy hunting was part of that ethos. Hunting was often seen as a noble activity, and by documenting species, it was believed they were helping preserve them in the long run.

- Absence of Modern Conservation Ideals: In the early 20th century, ideas of conservation were far less developed than today. Efforts to protect ecosystems or prevent extinction were often secondary to the desire for exploration and trophy hunting. Conservation then focused more on resource management than on preserving animals for their intrinsic ecological value.

- Establishing Protected Areas: Ironically, some of the early hunters and explorers who engaged in large-scale killing were instrumental in the eventual creation of protected areas. Theodore Roosevelt, for example, became one of the most influential figures in the establishment of national parks in the U.S. His experiences in Africa helped shape his views on protecting wilderness, even though his safari involved the killing of thousands of animals.

The Imperial Romance of Safaris

These early 20th-century figures were instrumental in romanticizing and popularizing the African safari among Western audiences. Their adventures, writings, and hunts contributed to the image of Africa as a wild, untamed frontier—a place for daring men and women to test their mettle against nature’s fiercest creatures. While their exploits contributed to the mystique of the safari, they also had profound and often destructive impacts on Africa’s wildlife, a legacy that continues to affect conservation efforts today. Their stories, however, live on in popular culture, shaping our understanding of what it means to venture into the African wilderness.

The Imperial Romance of Safaris

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, African safaris became closely tied to the notion of imperial romance, a blend of adventure, conquest, and the exotic allure of the African wilderness. European colonial powers, particularly the British, viewed Africa as an untamed frontier—rich in wildlife, landscapes, and natural resources—ripe for exploration and dominance. Safaris during this period were seen as a noble pursuit, and big-game hunting became a symbol of masculinity, status, and conquest.

Prominent figures such as Theodore Roosevelt, Frederick Selous, and Ernest Hemingway helped popularize the safari as a glamorous, adventurous endeavor. Safari-goers, typically wealthy Europeans and Americans, ventured into Africa on expeditions that involved killing large game like lions, elephants, and rhinos. The “imperial” aspect of the safari emphasized control over nature, with hunters often taking pride in their dominance over African wildlife, mirroring the colonial relationship between European powers and African lands.

These expeditions were also seen as a form of exploration, with the hunting of animals often portrayed as a heroic act of taming the wild and documenting exotic species for science and museums. The killing of game was considered part of the natural order, a demonstration of man’s supremacy over nature, and a way to collect trophies that symbolized both personal achievement and Western dominance over Africa.

Safari word Transition to Embody True Conservation Free of Big Game Hunting

By the mid-20th century, attitudes toward wildlife and conservation began to shift dramatically. This change was driven by several factors:

- Decline in Wildlife Populations: Large-scale hunting expeditions and the unregulated killing of big game led to sharp declines in many iconic species. Elephants, rhinos, and lions were particularly affected, which prompted growing concerns about their long-term survival.

- The Rise of Scientific Conservation: As scientific knowledge about ecosystems expanded, there was a growing understanding of the importance of preserving species, not for trophies, but for their ecological roles. The idea of “conservation” began to move away from regulated hunting and resource management toward protecting entire ecosystems and preventing the extinction of species.

- The Creation of National Parks and Reserves: African nations, particularly Kenya and Tanzania, began establishing national parks and game reserves where hunting was banned or strictly regulated. Parks like the Serengeti, Masai Mara, and Amboseli became refuges for wildlife, focusing on preservation and eco-tourism rather than hunting. These parks helped transition the concept of safari from big-game hunting to wildlife observation and photography.

- Influence of Conservationists: Figures like David Attenborough, Jane Goodall, and Richard Leakey emerged as champions of true conservation. They emphasized the ethical and ecological importance of protecting wildlife, raising global awareness of the dangers posed by poaching, habitat destruction, and hunting.

- Safari Rebranding: By the late 20th century, safaris had been rebranded to emphasize eco-tourism, where visitors could observe Africa’s wildlife in its natural habitat without causing harm. Modern safaris now promote sustainable tourism, where protecting wildlife and supporting local conservation efforts are at the heart of the experience.

From Hunting to Eco-Tourism

The meaning of safari underwent a significant transformation as conservation efforts grew. The imperial romance of the early safaris—centered on dominance and trophy hunting—gave way to an emphasis on true conservation, where the focus shifted to wildlife preservation and the ethical treatment of animals. Today, a safari is no longer about hunting and conquering the African wilderness, but rather about appreciating and conserving it. Modern safaris provide opportunities to experience the beauty of Africa’s diverse ecosystems while supporting efforts to protect them for future generations.

This evolution reflects a broader shift in global attitudes toward conservation, as societies increasingly recognize the need to protect natural environments and species from exploitation. While the historical roots of the safari are tied to colonialism and hunting, its modern form embodies a respect for nature and a commitment to sustainability.

Modern-Day Safari: A Shift Toward Conservation and Ethical Wildlife Viewing

Today, safaris are no longer associated with the large-scale killing of animals that defined the expeditions of the early 20th century. Instead, modern-day safaris are centered around wildlife conservation, eco-tourism, and sustainable practices that support both the protection of African wildlife and the local communities. The emphasis is on game driving, a responsible way to view and appreciate wildlife in its natural habitat without disturbing or endangering the animals. This evolution marks a stark contrast to the hunting-based safaris of the past.

Key Features of Modern-Day Safari

- Conservation-Focused Tourism: Modern safaris are designed to minimize the environmental impact while maximizing the educational and emotional connection with nature. National parks and game reserves like the Masai Mara, Serengeti, and Kruger National Park have established strict regulations that prioritize the welfare of wildlife. Many safari operators now contribute a portion of their profits to conservation efforts and local communities, ensuring that tourism has a positive impact.

- Wildlife Viewing and Photography: Safaris today focus on wildlife observation and photography, with game drives allowing visitors to witness Africa’s famous species—such as lions, elephants, and rhinos—without disrupting their natural behavior. Safari vehicles are typically designed to offer optimal game viewing while maintaining a safe distance from the animals. Unlike past safaris, where animals were hunted for trophies, today’s travelers seek to capture the beauty of wildlife through the lens of a camera, emphasizing preservation over exploitation.

- Guided Experiences by Professional Naturalists: Professional guides, often highly trained in ecology and animal behavior, lead modern safaris, offering educational insights into the ecosystem and the importance of conservation. These guides help guests understand the delicate balance of nature and the role that each species plays within it. This educational component encourages respect for wildlife and promotes a greater understanding of conservation challenges.

- Sustainable Practices: Many modern safari lodges and camps are now designed with eco-friendly infrastructure, including solar power, rainwater harvesting, and waste recycling. These sustainable practices reduce the environmental footprint of tourism and promote long-term protection of wildlife habitats. Ethical safari operators also follow strict guidelines to ensure that vehicles do not off-road excessively or damage sensitive ecosystems.

Types of Safaris: A Journey into the Heart of Africa’s Wilderness

Modern safaris offer a range of experiences, each designed to connect travelers with the wonders of African wildlife and landscapes in unique ways. Whether it’s traversing the vast savannas in a 4×4 vehicle or floating above the plains in a hot air balloon, there’s a safari experience to suit every type of adventurer. Here’s a look at the diverse types of safaris available today:

1. Classic Wildlife Safaris

The quintessential African safari involves a journey through national parks and game reserves in a specialized off-road vehicle, led by an experienced driver-guide. These safaris take travelers deep into the natural habitats of Africa’s most iconic wildlife. From herds of elephants, zebras, and buffalo roaming the grasslands to majestic giraffes grazing on treetops, a classic wildlife safari offers breathtaking encounters with large herbivores. Alongside them are predators like lions, leopards, and cheetahs stalking their prey, while jackals and hyenas scavenge or hunt smaller animals. Safari-goers witness these interactions in real-time, creating unforgettable memories of life in the wild.

2. Balloon Safaris

For a truly magical experience, balloon safaris provide a peaceful, aerial perspective of the African landscape. At dawn, travelers drift silently over the plains in a hot air balloon, watching as the sun rises and herds of animals move gracefully across the land below. This safari is ideal for photographers, offering stunning panoramic views and the chance to spot wildlife that might be missed on the ground. Balloon safaris are popular in places like the Masai Mara during the Great Migration, where visitors can witness vast herds of wildebeest and zebras from the sky.

3. Nature Walk Safaris

Walking safaris are perfect for those who want a more immersive and intimate experience with nature. Accompanied by professional guides and armed rangers, travelers walk through the bush, learning to track animals by their footprints and identifying various plants and smaller wildlife that often go unnoticed on vehicle safaris. Walking safaris allow a deeper connection to the environment, offering the thrill of being on the ground in the midst of the African wilderness. These safaris are especially popular in areas like Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park.

4. Fly-In Safaris

Fly-in safaris provide access to remote and pristine areas that are often difficult to reach by road. In a light aircraft, travelers fly directly to exclusive lodges or camps situated in isolated locations, such as the Okavango Delta in Botswana or the far reaches of the Serengeti. This safari option is perfect for those seeking privacy and a more personalized experience, as it allows guests to explore off-the-beaten-path destinations while avoiding the crowds found in more accessible parks.

5. Honeymoon and Vacation Safaris

For couples seeking romance and adventure, honeymoon safaris offer the perfect blend of luxury, privacy, and nature. Many safari lodges and camps cater specifically to honeymooners, offering private game drives, candlelit dinners in the bush, and luxurious accommodations in scenic settings. Whether it’s a sunset over the Serengeti or a candlelit dinner under the stars in the Masai Mara, honeymoon safaris are designed to create once-in-a-lifetime experiences for newlyweds.

Similarly, vacation safaris cater to families, groups, or individuals looking for a well-rounded experience that includes wildlife viewing, cultural interactions with local communities, and relaxation at luxury lodges. Many vacation safaris also offer customizable itineraries to suit the specific interests of the travelers, whether that’s photography, bird watching, or adventure activities.

6. Night Safaris

For those eager to see Africa’s nocturnal wildlife, night safaris offer an exciting opportunity to observe animals that are rarely seen during the day. Equipped with specialized spotlights, night drives reveal a different side of the bush as predators like lions and leopards become more active, hunting under the cover of darkness. Meanwhile, creatures such as aardvarks, porcupines, and bush babies make their nighttime appearances. Night safaris are often available in parks that permit after-dark driving, such as Kruger National Park in South Africa.

7. Boat Safaris

In regions with prominent rivers and lakes, boat safaris offer a unique way to observe wildlife from the water. Rivers like the Chobe in Botswana or Lake Naivasha in Kenya are home to hippos, crocodiles, and a variety of bird species. Travelers can glide along the water’s edge, watching animals like elephants and buffalos come to drink, while enjoying the serene beauty of Africa’s waterways.

8. Photographic Safaris

For photography enthusiasts, photographic safaris provide tailored experiences with expert guides who specialize in capturing wildlife. These safaris often involve private vehicles equipped with camera mounts and the opportunity to spend longer periods in one location, ensuring photographers can capture the perfect shot. Whether it’s a close-up of a lion on the prowl or a panoramic view of a herd of elephants, these safaris cater to both amateur and professional photographers.

Welcome to the Greater Mara-Serengeti Ecosystem: The Birthplace of Epic Safaris

Spanning Kenya and Tanzania, the Greater Mara-Serengeti Ecosystem is one of the most biodiverse regions in the world, home to Serengeti National Park, Ngorongoro Conservation Area, and Masai Mara National Reserve. Known for its breathtaking wildlife and conservation efforts, this region is the heart of the modern safari.

Serengeti National Park (Tanzania)

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Serengeti is famed for the Great Migration, where over 1.5 million wildebeest and 200,000 zebras move in search of grazing. The park is home to the Big Five and plays a vital role in conservation with anti-poaching efforts and habitat protection. The Mara River crossings and predator-prey interactions make it a safari highlight.

Ngorongoro Conservation Area (Tanzania)

Known for the Ngorongoro Crater, the world’s largest volcanic caldera, it shelters over 25,000 animals, including lions and the endangered black rhino. The area allows co-existence between Maasai pastoralists and wildlife, blending culture and conservation. The nearby Olduvai Gorge is a key archaeological site, contributing to its significance.

Masai Mara National Reserve (Kenya)

The Masai Mara is renowned for its role in the Great Migration and rich predator populations. Community-based conservation models, including private conservancies, allow locals to benefit from tourism while protecting wildlife. The Mara’s year-round game viewing and predator concentrations, including lions, leopards, and cheetahs, make it a premier safari destination.

When to go on a safari?

The best months for a safari largely depend on the destination and the type of wildlife experience you’re seeking. Here’s a guide to the best months for safaris in East and Southern Africa:

1. East Africa (Kenya & Tanzania)

- June to October: This is the dry season and considered the best time for safaris in the Masai Mara (Kenya), Serengeti (Tanzania), and other East African parks. Wildlife is easier to spot because the animals gather around water sources, and the grass is shorter, improving visibility. It’s also the prime time to witness the Great Migration in the Serengeti and Mara, especially the dramatic Mara River crossings (July to September).

- January to March: This is the calving season in the Southern Serengeti, when large numbers of wildebeest give birth. It’s an excellent time for predator action as lions, cheetahs, and other carnivores take advantage of the vulnerable newborns.

2. Southern Africa (Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe)

- May to October: These months are considered the best time for safaris in Southern Africa, including Kruger National Park (South Africa), Chobe National Park (Botswana), and Hwange (Zimbabwe). This is the dry season, and wildlife is concentrated around water sources, making it easier to spot large herds of elephants, buffalo, and predators. Visibility is excellent as the bush thins out.

- November to April: This is the green season or wet season, characterized by lush landscapes and fewer tourists. While the rains make some areas harder to access, this period offers great birdwatching, newborn wildlife, and lower prices. The Okavango Delta in Botswana is still a great destination during these months, especially for birding enthusiasts.

3. Best Time for Specific Experiences

- Great Migration in the Serengeti/Masai Mara: July to September (river crossings), January to March (calving season in the southern Serengeti)

- Botswana’s Okavango Delta: June to October (high water levels and dry season for game viewing)

- Zambia’s South Luangwa Walking Safaris: June to October (best conditions for walking safaris)

- Gorilla Trekking in Rwanda/Uganda: June to September and December to February (drier months for easier trekking)

In general, the dry season (typically June to October) is ideal for most safaris due to easier wildlife spotting and pleasant weather conditions. However, the wet season (November to April) offers unique experiences such as birdwatching, fewer tourists, and lush landscapes, making it worthwhile for some travelers.

What safaris embody the best of modern-day conservation efforts?

Several safaris around Africa not only offer unforgettable wildlife experiences but also embody the very best of modern-day conservation efforts. These safaris are centered on preserving natural ecosystems, supporting local communities, and protecting endangered species. Here are some of the most notable safari destinations and organizations that exemplify conservation excellence:

1. Lewa Wildlife Conservancy (Kenya)

Lewa Wildlife Conservancy is a prime example of a safari destination built around conservation. Once a cattle ranch, it is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a model for community-driven conservation. Lewa is famous for its successful rhino conservation program, which has helped increase populations of both black and white rhinos. Visitors to Lewa contribute directly to these efforts, and the conservancy also supports local communities through education, health programs, and employment opportunities.

- Conservation Focus: Rhino protection, endangered species conservation, community outreach.

- Best For: Rhino tracking, Big Five safaris, cultural engagement with local communities.

2. Ol Pejeta Conservancy (Kenya)

Ol Pejeta is one of the most well-known private conservancies in Africa, blending wildlife conservation with sustainable ranching. Home to the last two northern white rhinos on earth, Ol Pejeta is also a sanctuary for critically endangered black rhinos and chimpanzees rescued from the pet trade. The conservancy focuses heavily on anti-poaching efforts, employing advanced technology like drones, canine units, and rapid-response teams to combat wildlife crime. The income generated from safari tourism helps fund these initiatives.

- Conservation Focus: Anti-poaching, northern white rhino conservation, community development.

- Best For: Big Five game drives, rhino tracking, chimpanzee sanctuary visits.

3. Singita Grumeti Reserves (Tanzania)

Located in the Western Corridor of the Serengeti, Singita Grumeti is a private concession dedicated to conservation and sustainable tourism. The reserve’s land, once overrun by poaching and unmanaged grazing, has been revitalized and now supports thriving populations of wildlife, including elephants, lions, and a large number of wildebeest during the Great Migration. Singita Grumeti’s Singita Grumeti Fund works extensively with local communities, providing jobs, educational programs, and support for small businesses, ensuring that conservation benefits both the wildlife and the people.

- Conservation Focus: Community empowerment, sustainable tourism, habitat restoration.

- Best For: Luxury safaris, Great Migration viewing, conservation education.

4. South Luangwa National Park (Zambia)

South Luangwa is the birthplace of the walking safari, offering an immersive way to explore the African wilderness while learning about conservation efforts. The park is managed under a community-focused approach, with a significant portion of tourism revenue reinvested into anti-poaching and wildlife protection programs. The Conservation South Luangwa (CSL) organization plays a vital role in protecting the park’s wildlife, particularly against the threat of poaching. It also works to minimize human-wildlife conflict in the surrounding communities.

- Conservation Focus: Anti-poaching, walking safaris, community involvement.

- Best For: Walking safaris, wildlife viewing, conservation-focused tourism.

5. Maasai Mara Conservancies (Kenya)

The Maasai Mara Conservancies are a series of private reserves that surround the Maasai Mara National Reserve. These conservancies have pioneered a unique conservation model that involves leasing land from the local Maasai communities in exchange for tourism revenue. This approach gives the Maasai economic incentives to protect the land and wildlife, creating a win-win situation where both people and animals benefit. Tourism within the conservancies is carefully managed to reduce the environmental impact, with low visitor numbers and sustainable practices in place.

- Conservation Focus: Community-driven conservation, wildlife protection, sustainable tourism.

- Best For: Great Migration viewing, predator sightings, cultural immersion with the Maasai.

6. Phinda Private Game Reserve (South Africa)

Phinda Private Game Reserve is a leading example of modern conservation in South Africa. Run by &Beyond, it was one of the first reserves to reintroduce the cheetah to the region and now boasts a thriving population of the species. Phinda is also known for its successful black rhino translocation program, which has helped grow rhino populations in South Africa. The reserve actively engages with local Zulu communities, providing jobs, education, and healthcare, ensuring that tourism benefits local people as much as it does wildlife.

- Conservation Focus: Cheetah and rhino conservation, habitat restoration, community engagement.

- Best For: Big Five safaris, luxury lodges, conservation-focused experiences.

7. Desert Rhino Camp (Namibia)

Desert Rhino Camp, located in the vast, rugged wilderness of Damaraland, offers a unique safari experience focused on the conservation of desert-adapted black rhinos. Managed by Wilderness Safaris in partnership with Save the Rhino Trust, this camp uses income from tourism to support rhino monitoring and protection programs. Rhino tracking on foot is a key activity here, and guests learn about the critical work being done to save these rare animals from poaching. The program’s success has turned Namibia into a leading example of rhino conservation.

- Conservation Focus: Rhino conservation, sustainable tourism, desert ecosystems.

- Best For: Rhino tracking, off-the-beaten-path safaris, conservation engagement.

8. Okavango Delta (Botswana)

The Okavango Delta, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the most pristine wilderness areas in Africa. It is renowned for its conservation success, largely due to the low-impact tourism model implemented in Botswana. The Okavango Community Trust ensures that local communities benefit from tourism, while wildlife and habitats are preserved through careful regulation and sustainable practices. The delta is home to a diverse array of species, including lions, elephants, hippos, and a wealth of birdlife.

Best For: Water-based safaris, bird watching, exclusive lodges.

Conservation Focus: Low-impact tourism, community involvement, sustainable resource management.