The Maasai Mara National Reserve (MMNR), often referred to as the Jewel in the Crown of Kenya’s protected areas, is renowned for its Great Wildebeest Migration and its exceptional biodiversity. However, this globally significant ecosystem is currently facing severe and escalating threats that jeopardize its ecological integrity, cultural heritage, and long-term economic sustainability. These challenges, outlined in the Maasai Mara Management Plan (2023) and supported by various academic studies, highlight the urgent need for coordinated conservation efforts and sustainable tourism practices.

1. Declining Wildlife Populations

One of the most alarming issues facing the Maasai Mara is the steep decline in key wildlife species, including both herbivores and carnivores. According to the management plan, many of these species are essential for the ecological balance of the Reserve and form the backbone of the Mara’s tourism product.

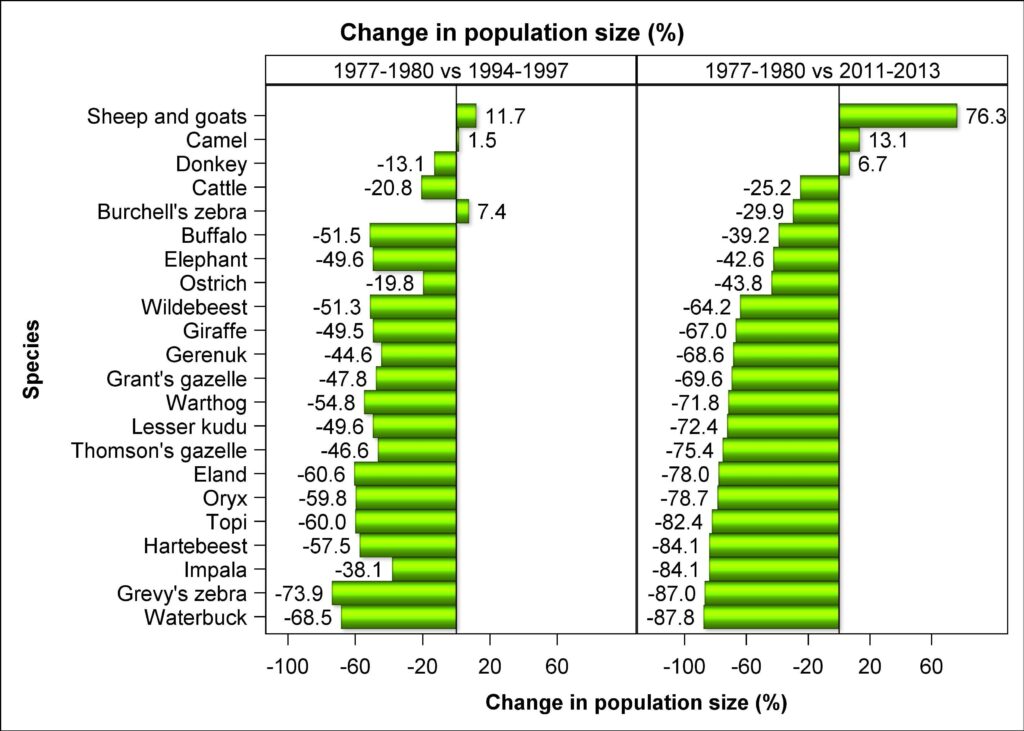

A study by Ogutu et al. (2016) found that populations of species such as zebras, giraffes, and warthogs have declined by over 70% in recent decades. Similarly, lion populations have been shrinking due to habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and poaching. The continued decline of these species not only impacts biodiversity but also threatens the Reserve’s appeal to tourists, which in turn affects the local economy.

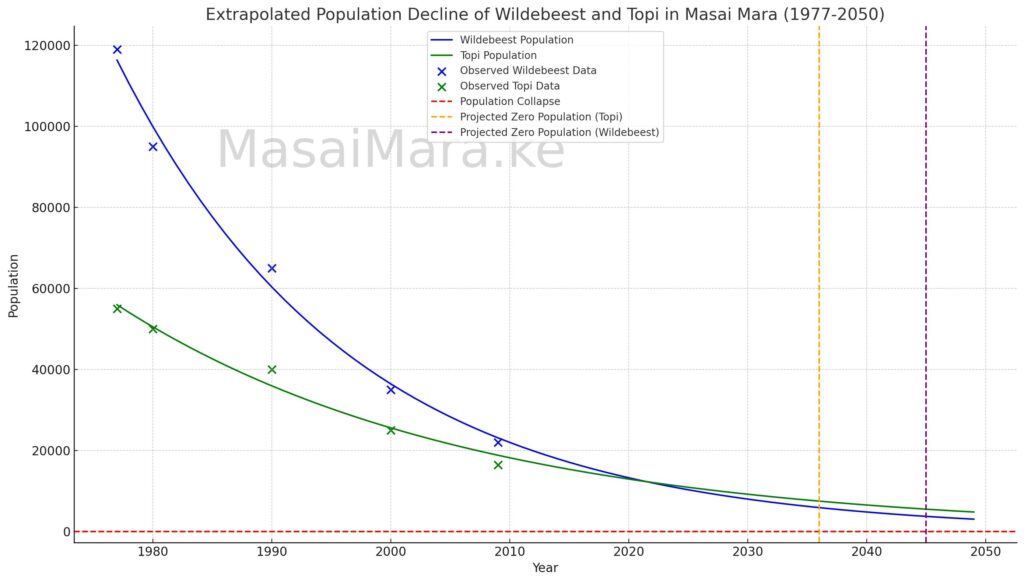

Specifically, data used in the research shows that between 1977 and 2009, the wildebeest population in the Masai Mara plummeted from about 119,000 to 22,000, while topi numbers fell from 55,000 to 16,500. Both species experienced a dramatic decline of over 70% in just three decades, reflecting a steady and alarming downward trend.

The chart illustrates the declining population trends of two key herbivore species in the Masai Mara ecosystem—wildebeest and topi—from 1977 to 2009 with extrapolated projections up to 2050. The alarming trend suggests that without effective conservation interventions, both species could face population collapse within the next few decades.

The chart below, based on the 2016 study, illustrates a widespread decline in wildlife populations across most species.

2. Diminishing Water Levels in the Mara River

The Mara River is the lifeblood of the Maasai Mara ecosystem, crucial for the survival of both resident wildlife and the wildebeest migration. However, reduced water levels and increasingly seasonal flows pose a serious threat to the Reserve. The management plan highlights that without access to the river, the wildebeest migration could collapse, and resident species would be critically impacted.

The Mau Forest Complex, which forms the primary catchment area of the Mara River, has suffered from deforestation and land conversion. According to Mwangi et al. (2018), illegal logging and farming have significantly reduced forest cover, leading to erratic water flow and soil erosion. Without immediate intervention, the Mara River’s ecosystem could be irreversibly altered, affecting both wildlife and local communities.

3. Overcrowding and Deteriorating Visitor Experience

Tourism is a double-edged sword for the Maasai Mara. While it generates significant revenue, overcrowding and unsustainable tourism practices are degrading the very environment that attracts visitors. The management plan notes that during the wildebeest migration, more than 150 vehicles have been recorded at a single Mara River crossing. Such congestion leads to wildlife harassment, habitat degradation, and a poor visitor experience.

A study by Van der Duim et al. (2015) emphasizes that mass tourism in protected areas can lead to environmental degradation and a decline in the quality of tourism products. If the Maasai Mara continues to be perceived as an overcrowded destination, it risks losing its competitive edge in the global tourism market.

High Visitor Density;

There is high visitor density in the Maasai Mara National Reserve (MMNR), with Central Mara seeing 2,074 visitors daily at 1.93 visitors/km², compared to 593 visitors at 1.22 visitors/km² in the Mara Triangle. Between 2009-2010, the Greater Mara Ecosystem had 140 tourism facilities with 4,145 beds, reflecting intense tourism pressure. MMNR’s visitor densities exceed those of Meru, Tsavo, and Amboseli, highlighting the need to manage tourism to protect the ecosystem while maintaining a quality visitor experience.

4. Unregulated Tourism Infrastructure Development

The Maasai Mara’s surroundings have seen a rapid increase in tourism accommodations, often unregulated and poorly planned. The management plan highlights that back-to-back lodges and camps along the Reserve’s borders have created a hard edge, preventing wildlife movements and occupying important habitats like riverine forests.

The Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association (KWCA) reports that the Greater Mara Ecosystem is under threat from uncontrolled development, which reduces wildlife dispersal areas and migration corridors. This fragmentation of habitats makes it harder for wildlife populations to thrive and increases human-wildlife conflicts.

5. Poaching and Livestock Grazing

Although poaching in the Maasai Mara has decreased compared to previous decades, it remains a persistent threat, particularly for high-value species such as elephants and rhinos. The management plan notes that livestock grazing within the Reserve is another critical issue, disrupting wildlife and altering the ecosystem.

Patterson et al. (2018) found that illegal grazing in protected areas can lead to competition for resources, disease transmission, and habitat degradation. In the Maasai Mara, livestock grazing not only impacts wildlife behavior but also undermines the tourism product, as tourists expect to see untamed wilderness rather than domestic animals.

6. Inadequate Management Infrastructure and Systems

The Maasai Mara’s management infrastructure has fallen behind that of comparable protected areas. The management plan points to insufficient resources, equipment, and professional systems, making it challenging for Reserve managers to address emerging threats.

A study by De Vos et al. (2019) highlights the importance of adaptive management systems in protected areas, emphasizing that without the flexibility to respond to new challenges, conservation efforts are likely to fail. The Maasai Mara urgently needs modernized management systems and increased investment to ensure long-term sustainability.

7. Visitor Carrying Capacity and Zonation

To address overcrowding and environmental degradation, the management plan introduces a Visitor Carrying Capacity and Zonation Scheme. This scheme divides the Reserve into four zones:

- High Use Zone: Areas with the most visitors, focusing on enhancing wildlife viewing experiences.

- Low Use Zone: Less frequented areas, emphasizing environmental protection.

- Mara River Zone: A sensitive ecological area requiring strict protection.

- Buffer Zone: A 2-km strip around the Reserve to control tourism impacts.

Implementing this scheme is crucial for balancing tourism and conservation. According to Buckley (2020), carrying capacity models are essential for maintaining ecological integrity in heavily visited protected areas.

8. Community Involvement and Livelihoods

The Maasai Mara’s long-term sustainability depends on local community support. The management plan recognizes the importance of community outreach programs to improve livelihoods and reduce reliance on unsustainable practices.

Research by Western et al. (2015) found that community-based conservation models are more successful when local people benefit economically from conservation efforts. The Mara Conservancies, which operate outside the Reserve, offer a successful model of low-density, high-value tourism, providing direct financial benefits to local communities.

Land Use & Land Tenure Changes

- Fragmentation of Rangelands:

Since the 1970s, communal Maasai group ranches have been subdivided into smaller plots averaging 60 hectares each, now often sold or leased to commercial agriculture or speculators. - Loss of Wildlife Corridors:

Key wildlife dispersal areas have been lost to farming and settlements. Recent studies in Enonkishu Conservancy show forest cover dropped by 92% in the last 20 years, while cultivated and grassland areas have increased by 97% and 90% respectively. - Pressure from Livestock:

In Mara North Conservancy, innovative lease models provide income to 750 Maasai landowners, but many invest these earnings in more livestock, further increasing grazing competition with wildlife.

Climate Change Impacts

- Decreased Rainfall & Increased Drought:

The Mara’s mean annual rainfall is 950 mm (range: 800–1200 mm), but studies now show declining rainfall and rising temperatures. This is leading to increased frequency of droughts and unpredictable rainy seasons. - Ecosystem at Risk:

Shorter rainy seasons mean water sources dry up faster, causing acute water scarcity and heightened competition for pasture among livestock and wildlife. For instance:- Drying of seasonal streams and wells

- Disruption of livestock breeding and higher disease incidence

- Impact on Wildlife and Tourism:

These changes alter wildlife migratory patterns, leading to loss of habitat, declines in biodiversity, and direct hits to tourism—the region’s economic lifeline. In 2012, the main highway to the Reserve closed for three days due to flooding, highlighting the vulnerability of infrastructure.

Conclusion

The Maasai Mara faces grave challenges that threaten its biodiversity, cultural heritage, and economic future. Addressing these issues requires urgent, coordinated action from all stakeholders, including government agencies, conservation organizations, local communities, and tourism operators. The Maasai Mara Management Plan (2023) provides a comprehensive framework for tackling these challenges through sustainable tourism practices, enhanced management systems, and community engagement.

If these efforts are not implemented swiftly, the Maasai Mara risks losing its status as one of the world’s greatest natural wonders. However, with proper planning, investment, and stakeholder cooperation, the Reserve can be preserved for future generations while continuing to provide significant economic benefits to the Maasai people and Kenya as a whole.