The Ultimate Guide to Africa’s Greatest Wildlife Spectacle

Every year, a vast wave of life moves across the East African plains—a natural rhythm so grand it can be seen from space. This is the Great Migration, an epic journey of over 1.3 million wildebeest, 200,000 zebras, and 400,000 gazelles that circle through the Serengeti–Masai Mara ecosystem in search of green pastures and rain.

The Masai Mara, on Kenya’s southwestern border, forms the northernmost stage of this endless journey. Between July and October, this landscape becomes the arena for one of nature’s most dramatic events—the Mara River crossings—where vast herds brave crocodile-infested waters and predators wait on both banks.

For travelers, photographers, and scientists alike, this is Africa’s greatest natural show—a breathtaking mix of movement, danger, and renewal that defines the Masai Mara ecosystem.

🌍 What Exactly Is the Great Migration?

The Great Migration is not a single event but a continuous, circular movement of herbivores that follows rainfall and grass growth across the Serengeti (Tanzania) and Masai Mara (Kenya). The herds travel a rough loop of over 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) each year, driven by one instinct: survival through feeding and reproduction.

This migration is unique because:

- It is driven by ecological cues (rainfall, vegetation, and nutrient cycles).

- It sustains entire predator guilds (lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, crocodiles).

- It has continued uninterrupted for hundreds of thousands of years, making it one of Earth’s last intact large-mammal migrations.

The Serengeti–Mara system acts as a single ecosystem, with animals moving freely across the Kenya–Tanzania border—though climate change, fencing, and settlement expansion are slowly challenging that connectivity.

Migration vs. Dispersal — Why the Great Migration Is Unique

The Great Migration is a textbook example of true migration—a predictable, seasonal, and cyclic movement driven entirely by shifting resources. Wildebeest, zebras, and gazelles move together in a synchronized loop each year, following rainfall, fresh grazing, and water. They return to the same regions annually and rely on remarkable endurance and the ability to sense distant rains.

In contrast, dispersal is a one-way, irregular movement of individuals or small groups, usually triggered by competition, crowding, or the search for new territory—such as young male lions leaving a pride. There is no return journey and no large-scale synchronization.

This distinction matters: migration requires open, connected landscapes, making the Serengeti–Mara one of the last ecosystems where such long-distance movement remains intact.

🔬 The Science Behind the Migration

From Facilitation to Competition

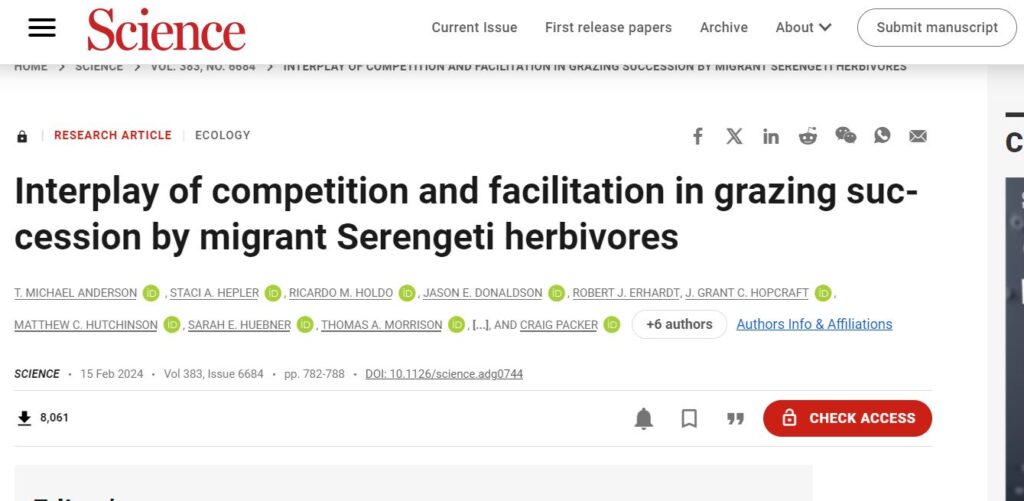

For decades, scientists believed migration followed a “facilitation sequence”: zebras grazed tall grass, wildebeest followed to eat medium shoots, and gazelles finished with short herbs. But groundbreaking 2024 research by Professor T. Michael Anderson (Wake Forest University, published in the Journal of Science) overturned that idea.

His team used camera traps, GPS collars, satellite data, and DNA diet analysis to show that competition, not cooperation, primarily drives migration patterns.

- Wildebeest, being the most numerous, dominate grazing areas and push zebras ahead of them to claim the richest patches first.

- Zebras must move faster and stay ahead, not to “prepare” the way, but to avoid being left with poor forage.

- Thomson’s gazelles come last—not as a consequence of being weaker, but because they feed on forbs and herbs that thrive after taller grasses are grazed down.

This dynamic is known as the “push-pull hypothesis,” showing that both competition and facilitation are at play in maintaining the Serengeti–Mara’s delicate ecological balance.

Population Dynamics

- Wildebeest numbers: ~1.3 million, with 400,000 calves born annually.

- Zebras: ~200,000, forming smaller sub-herds that mix with wildebeest.

- Gazelles: ~400,000, often forming trailing groups that follow in the wake of grazed areas.

- Predators: Lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, jackals, and crocodiles synchronize breeding and hunting patterns with migration peaks.

📅 Month-by-Month Breakdown of the Migration

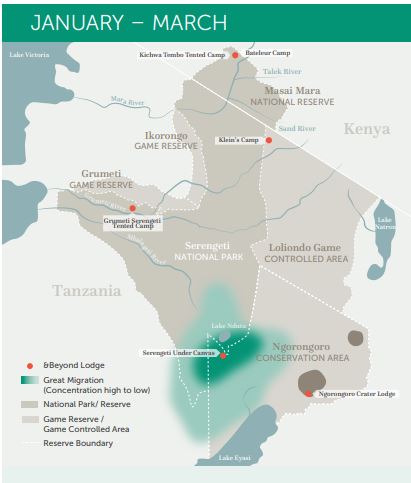

January – March: Calving Season (Southern Serengeti Plains)

This is where life begins. In the nutrient-rich short-grass plains around Ndutu and Ngorongoro, over 500,000 wildebeest calves are born in just a few weeks.

Why here: The soil’s volcanic minerals make the grass highly nutritious, essential for lactating mothers and young calves.

What you’ll see:

- Newborn wildebeest taking their first steps within minutes of birth.

- High predator activity—especially lions and cheetahs.

- Migratory birds and lush green scenery perfect for photography.

April – May: The Long March North (Central & Western Serengeti)

As the long rains fall, herds break into splinter groups moving through Seronera and the Grumeti River corridor. The ground is lush but muddy, making movement slow and scattered.

Highlights:

- Long, scenic game drives with herds as far as the eye can see.

- Great predator sightings, especially leopards in the central Serengeti.

- Ideal for travelers who prefer fewer crowds and greener landscapes.

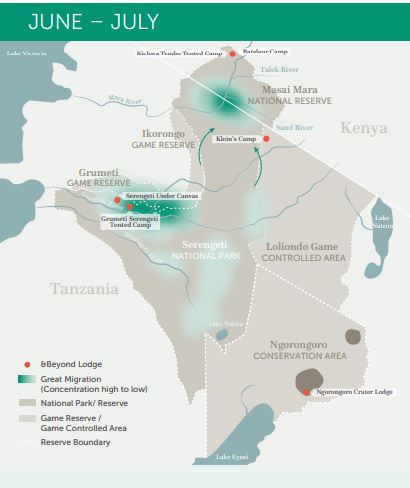

June – July: The Grumeti Crossings & Northern Push

By June, the herds gather in the Western Corridor, where they face their first major obstacle—the Grumeti River. These crossings are smaller than the Mara’s but no less dramatic, with giant Nile crocodiles waiting below.

Wildlife highlights:

- Elephants, giraffes, lions, and buffalo following the herds.

- Rich birdlife and stunning golden plains.

By late July, the front edge of the migration enters Kenya’s Masai Mara, crossing near the Sand River and Mara Triangle.

July – October: The Masai Mara & The Legendary River Crossings

This is the heart of the Great Migration—the Mara phase that draws travelers from all over the world.

Where the action happens:

- Mara River: Between Serena, Lookout Hill, and Purungat Bridge—the main crossing points.

- Mara Triangle: Best for fewer crowds, clear photography, and excellent predator sightings.

- Musiara Marsh & Talek River: Great for general game and big cats.

Expect to see:

- Thousands of wildebeest plunging into the river, sometimes several times a day.

- Lions ambushing at crossing exits.

- Crocodiles lying in wait below.

- Massive herds moving like living waves across the plains.

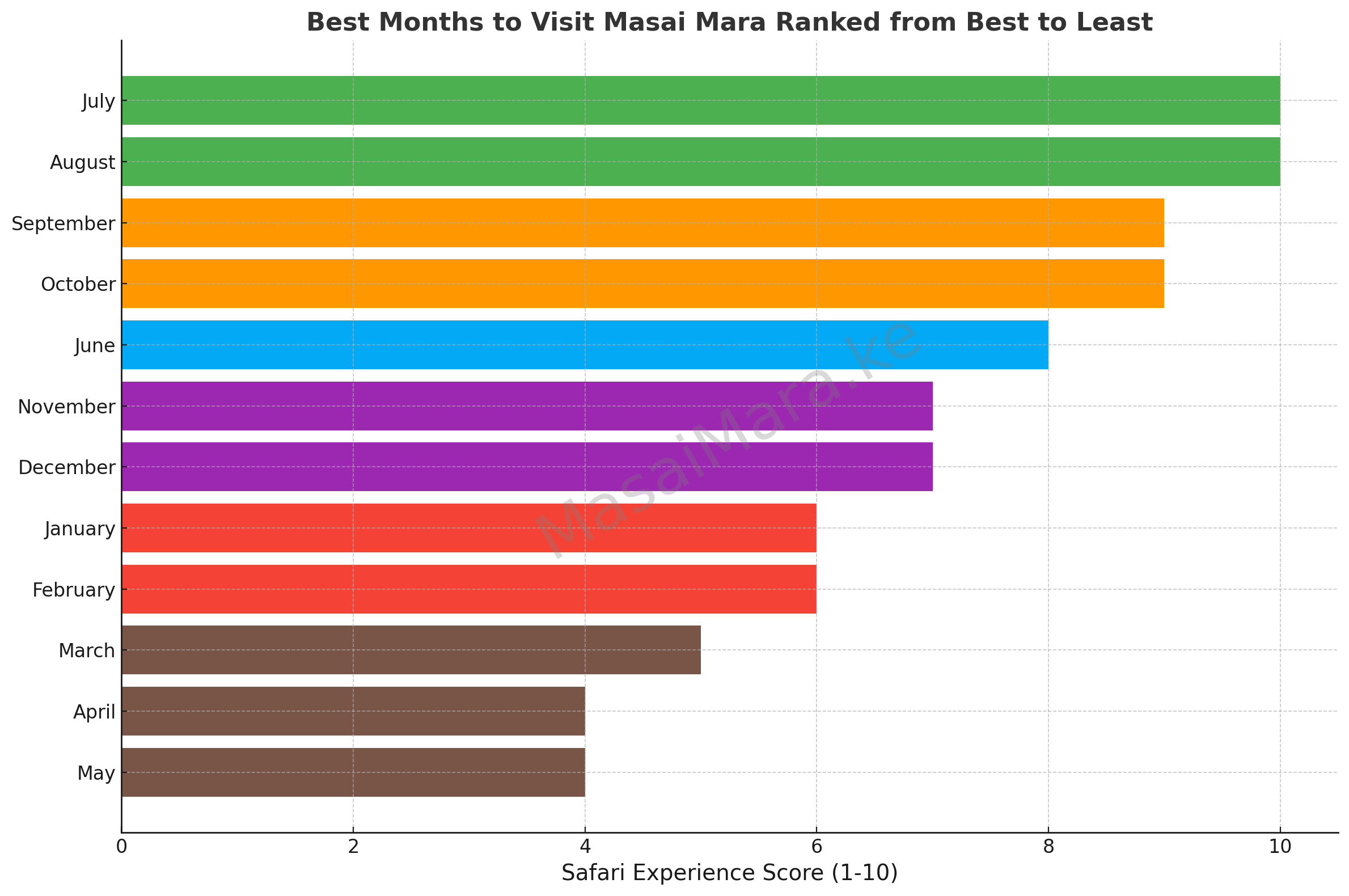

Best time to visit:

Late July to early October, though timing depends on rainfall.

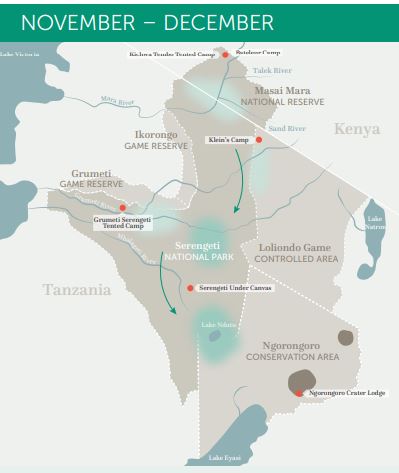

November – December: The Journey South Begins

With the onset of short rains, the herds gradually return to Tanzania. Smaller groups move south through Lobo, Kusini, and Seronera, feeding along the way.

What you’ll see:

- Fewer tourists, lush landscapes, and scattered wildlife.

- Big cats following the departing herds.

- A quieter, more reflective end to the migration cycle.

🌾 Ecology & Environment: How the Migration Shapes the Mara

The Great Migration isn’t just about animal movement—it’s a landscape-level process that keeps the entire savanna alive.

Key Ecological Roles

- Grass regeneration: Grazing and dung fertilize the soil, creating a nutrient cycle that rejuvenates pastures.

- Predator–prey balance: Predator populations are naturally regulated by the presence and density of herds.

- Seed dispersal: Hooves and droppings spread seeds across hundreds of kilometers, aiding plant diversity.

Climate & Environmental Change

- Rainfall drives everything: When rains fail or arrive early, migration timing shifts dramatically.

- Climate change: Prolonged droughts and unseasonal rains are making movement less predictable.

- Fencing & development: Expanding agriculture and fences around migration corridors threaten the ancient routes herds depend on.

🦁 Wildlife Encounters

- Lions: Up to 35 prides roam the Mara, specializing in hunting during migration months.

- Cheetahs: Found on open plains, especially in Olare Motorogi and Naboisho conservancies.

- Leopards: Secretive but often seen near riverine forests.

- Hyenas: Efficient hunters and scavengers, not just “clean-up crews.”

- Crocodiles & Hippos: Dominant in the Mara River ecosystem; crocodiles synchronize feeding with crossings.

🗺️ Where to See the Migration in the Masai Mara

- Mara Triangle (Oloololo side):

- Managed by the Mara Conservancy.

- Lower vehicle density, ideal for river crossings and photography.

- Musiara & Talek areas:

- Classic Mara scenery; excellent for lions, cheetahs, and resident wildlife.

- Ol Seki & Naboisho Conservancy:

- Bordering the Reserve; offer walking safaris, night drives, and fewer tourists.

- Sand River region:

- Where herds often enter Kenya from Tanzania.

🚙 Planning Your Safari

How to Get There

- By air: Daily flights from Nairobi’s Wilson Airport to Mara airstrips (Serena, Musiara, Ol Seki).

- By road: 5–6 hours from Nairobi via Narok and Sekenani Gate.

Where to Stay

- Luxury lodges: Angama Mara, Mara Serena, Entim Camp.

- Mid-range camps: Kambu Mara Camp, Ashnil, Fig Tree.

- Budget options: Community campsites and eco-tents.

- Mobile camps: Move seasonally to stay close to the herds.

Best Duration

Stay at least 3–4 nights—ideally 5 or more—to maximize your chance of seeing a crossing.

Recommended Activities

- Full-day game drives: Cover multiple zones in search of herds.

- Hot-air balloon safaris: Dawn flights over the Mara River and plains.

- Walking safaris (in conservancies): Learn about tracks, insects, and plants.

- Cultural visits: Engage with Maasai communities and their conservation role.

10 Incredible Facts About the Wildebeest Migration

- The Migration is a year-round cycle, with herds moving continuously between Serengeti and Masai Mara following rainfall and grass growth.

- Over 1.5 million wildebeest and 200,000 zebras participate, forming the largest land-mammal migration on Earth.

- Mara River crossings (Jul–Oct) are the most dramatic phase, involving mass drownings, crocodile attacks, and unpredictable herd surges.

- Wildebeest navigate using “swarm intelligence,” responding to neighbors rather than a leader, which keeps herds cohesive and predator-resistant.

- The migration route is predator-dense, with lions, hyenas, cheetahs, leopards, wild dogs, and giant crocodiles exploiting the moving herds.

- Calving season produces 500,000 newborns in weeks, flooding the plains with vulnerable calves and triggering intense predator activity.

- Rain—not predators—drives movement, as wildebeest detect distant storms and track the greening of fresh, nutrient-rich grass.

- Wildebeest and zebras cooperate, with zebras clearing tough grass and offering sharp sight while wildebeest contribute superior hearing and smell.

- Roughly 250,000 wildebeest die annually through predation, drowning, exhaustion, and stampedes, a natural cost of the migration.

- Recognized as one of Africa’s Seven Natural Wonders, the Great Migration is best viewed in Masai Mara from July to October during peak crossings.

🧠 Frequently Asked Questions

Is the Great Migration predictable?

Not perfectly—it’s tied to rainfall, not dates. The general pattern repeats yearly, but exact weeks vary.

Can I see the migration year-round?

Yes, but different parts of it. The action moves across the Serengeti–Mara circuit through the year.

Which month is best to see river crossings?

Typically July–September, though crossings can occur anytime during dry-season months.

Is it crowded?

The Mara gets busy in peak season. Choosing a conservancy or the Mara Triangle helps avoid congestion.

Are the crossings guaranteed?

No, they’re spontaneous and depend on herd behavior. Patience—and time—are key.

How far in advance should I book?

At least 6–9 months for July–October. Balloon safaris sell out fastest.

Do I need park entry tickets?

Yes, purchase through eCitizen before arrival (Kenya Wildlife Service system).

Is it safe?

Yes. The Masai Mara is a well-managed, secure safari destination. Always follow guide instructions.

🛡️ Conservation, Culture & Responsibility

The Great Migration exists thanks to coexistence—between wildlife, Maasai pastoralists, and conservation initiatives.

- Community Conservancies: Maasai landowners lease grazing land for wildlife use, providing income and protecting corridors.

- Human–Wildlife Conflict: Projects now compensate for livestock loss and fund predator-proof bomas (enclosures).

- Sustainable Tourism: Limiting vehicle numbers, supporting eco-lodges, and avoiding overcrowding at crossings are vital for long-term balance.

The Masai Mara is also part of Kenya’s Key Biodiversity Areas (KBA), linking conservation, livelihoods, and tourism revenue to a single ecosystem goal: keeping the migration alive.

🧭 Geography, Biomes & Ecosystem Zones of the Masai Mara

The Masai Mara ecosystem covers roughly 1,510 km² within Kenya’s Narok County but connects to over 25,000 km² of continuous savanna when combined with Tanzania’s Serengeti. It isn’t a uniform plain; it’s a patchwork of habitats that influence how and where the herds move.

Key Ecosystem Zones

- Open Plains (Mara Triangle & Central Mara): Short, nutritious grasses that attract the bulk of the wildebeest herds.

- Riverine Forests: Along the Mara and Talek rivers—cooler micro-habitats for elephants, leopards, and birdlife.

- Acacia Woodland: Between Talek and Ol Seki; supports browsers such as giraffe and eland.

- Escarpments (Oloololo Ridge): Overlook viewpoints used by vultures and raptors; serve as natural migration barriers.

- Marshes (Musiara, Ngama): Permanent water and dense cover—critical refuges for resident animals during dry months.

Understanding these zones helps visitors and photographers anticipate wildlife movement even when the herds are scattered.

🌦️ Meteorology & Seasonality: How Rain Shapes the Migration

The Great Migration is powered by East Africa’s bimodal rainfall system—two rainy seasons that alternate across the equator.

| Season | Period | Typical Rainfall | Migration Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long Rains | March – May | 100–200 mm/month | Herds spread through central Serengeti; slower movement |

| Dry Season | June – Oct | Minimal | Concentration in northern Serengeti & Masai Mara |

| Short Rains | Nov – Dec | 50–100 mm/month | Start of southward return |

| Green Season | Jan – Feb | Light showers | Nutrient-rich grass supports calving |

Because the equatorial rain belt shifts north–south through the year, the Mara’s dry season coincides with the Serengeti’s lush period—precisely why the herds must cross the border.

Traveler takeaway: If rains arrive early, the herds may reach the Mara in June; if late, not until August. Real-time rainfall maps are the best predictors of where the herds will be.

📡 Migration Monitoring & Technology

The Serengeti–Mara is one of the most studied ecosystems on Earth, and modern tools have revolutionized our ability to follow the migration in real time.

Technologies Used

- GPS Collars: Hundreds of wildebeest and zebra are fitted with satellite transmitters to track routes and speed.

- Remote Sensing: NASA’s MODIS imagery detects vegetation greenness (NDVI), predicting where fresh grass will emerge.

- Camera Traps & AI: Machine-learning software now identifies individual animals, estimating population turnover.

- Acoustic Sensors: Researchers use passive microphones to measure herd density and even calf survival rates at night.

- Crowdsourced Sightings: Apps like HerdTracker combine traveler and pilot reports to produce live migration maps.

These technologies don’t just help tourists plan better—they inform conservation planning, border management, and emergency responses during droughts or floods.

🧑🏽🌾 Socio-Economic & Community Dimensions

Beyond its ecological fame, the migration sustains tens of thousands of livelihoods in Narok County and across northern Tanzania.

Economic Impact

- Tourism Revenue: The migration season generates an estimated US $250–300 million annually for Kenya’s economy.

- Employment: Guides, rangers, drivers, cooks, artisans, and farmers benefit directly or indirectly from safari tourism.

- Conservancy Leases: Maasai landowners receive regular payments for setting aside land for wildlife use, stabilizing household income.

Community Challenges

- Balancing livestock grazing with wildlife movement.

- Managing water use during drought.

- Preventing land subdivision and fencing that block corridors.

Many conservancies now blend eco-tourism, education, and cultural heritage—for example, youth programs that train Maasai rangers or bead-work cooperatives that supply safari lodges.

🧠 Research Highlights & Ongoing Questions

Scientists continue to use the Mara as a living laboratory to understand large-scale migrations. Current research focuses on:

- Migration & Carbon Cycling: How herbivore movements influence greenhouse-gas balance in savanna soils.

- Predator Adaptation: How lions and hyenas adjust territory sizes as herds fluctuate.

- Corridor Connectivity Modeling: Identifying which private lands are most critical to keep open for future herd movement.

- Genetic Flow: Using DNA from dung samples to study how gene exchange across borders maintains population resilience.

- Climate-Migration Coupling: Predictive models testing how 1–2 °C temperature rise might shift the timing by 10–15 days.

🏕️ Visitor Experience: Beyond the River Crossings

Most travelers come for the crossings, but the migration experience extends far beyond that spectacle.

Alternative Experiences

- Predator-tracking Drives: Following big-cat hunts in early morning light.

- Night Drives (in Conservancies): See civets, servals, and aardwolves.

- Walking Safaris: Learn about insects, medicinal plants, and spoor interpretation.

- Aerial Photography: Charter flights or drones (where legal) offer cinematic views of herd formations.

- Citizen Science Safaris: Some lodges partner with researchers—guests help record animal IDs or upload sightings to databases.

Best Viewing Ethics

- Keep 25 m distance from animals.

- Limit vehicles per sighting (6 max in Mara Triangle).

- Use silent or low-rev engines; switch off when stationary.

- Avoid blocking herd paths at crossings—stress causes accidents and drownings.

🐾 Biodiversity Beyond the Big Herds

While the migration steals the spotlight, the Mara’s resident species form the ecosystem’s constant heartbeat.

- Mega-fauna: Elephants, buffalo, hippos, and giraffes remain year-round.

- Birdlife: Over 470 species, including secretary birds, crowned cranes, kori bustards, and raptors.

- Reptiles & Amphibians: Monitor lizards, Agama lizards, and the unique Mara toad.

- Pollinators: Butterflies and bees crucial for the acacia woodland regeneration that supports browsers.

Highlighting these layers enriches visitor understanding and reinforces the idea that conservation isn’t only about the herds—it’s about the entire web of life.

🪧 Governance, Policy & Transboundary Management

Protected-Area Management

- Masai Mara National Reserve: Managed by Narok County Government.

- Mara Triangle: Managed separately by the Mara Conservancy (a nonprofit model praised globally).

Regional Cooperation

The Serengeti–Mara Transboundary Initiative (SMTI) coordinates research, ranger patrols, and tourism policies between Kenya and Tanzania. It promotes:

- Harmonized park fees and regulations.

- Shared anti-poaching intelligence.

- Corridor mapping on both sides of the border.

Legal Framework

Kenya’s Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (2013) and Community Land Act (2016) provide the legal backbone for conservancies and revenue-sharing.

🧩 Environmental Threats & Future Outlook

Emerging Threats

- Fencing & Subdivision: Restricts ancient pathways; already visible near Loita and Mau escarpments.

- Overtourism: Too many vehicles at crossings disturb wildlife and erode riverbanks.

- Water Abstraction: Upstream agriculture reduces Mara River flow during dry months.

- Climate Extremes: Prolonged droughts shrink grazing range; floods drown calves.

Solutions Underway

- Re-opening corridors through community easements.

- Implementing vehicle-limit policies.

- Upstream catchment restoration (Mau Forest reforestation).

- Diversifying tourism beyond peak months to spread revenue.

The future of the Great Migration depends on maintaining landscape connectivity, managing tourism growth, and ensuring that local communities remain active partners in conservation.

🧭 Final Reflections

Watching the Masai Mara Great Migration isn’t just seeing animals—it’s witnessing the living pulse of Africa’s most resilient ecosystem. The thundering hooves, the swirl of dust, the tension at every riverbank—all tell the story of life’s determination to endure.

From scientific research reshaping our understanding of interspecies competition to community conservation ensuring the future of the plains, every dimension of the migration reminds us how deeply connected everything is—climate, culture, and conservation.

Whether you come as a photographer, nature lover, or first-time visitor, the key is to travel thoughtfully: give the animals space, respect the land, and support the people who protect it.