Enonkishu Conservancy is a community-owned wildlife conservancy within Kenya’s Greater Mara ecosystem, located along the northern boundary of the Masai Mara National Reserve (MMNR). It is widely recognised as a flagship example of integrated conservation, combining wildlife protection, regenerative grazing, research, and community livelihoods in a working rangeland.

Unlike conservancies focused primarily on tourism, Enonkishu is best known for its landscape-scale conservation and sustainable land-use model, making it one of the most influential conservancies in the Mara from a conservation and research perspective.

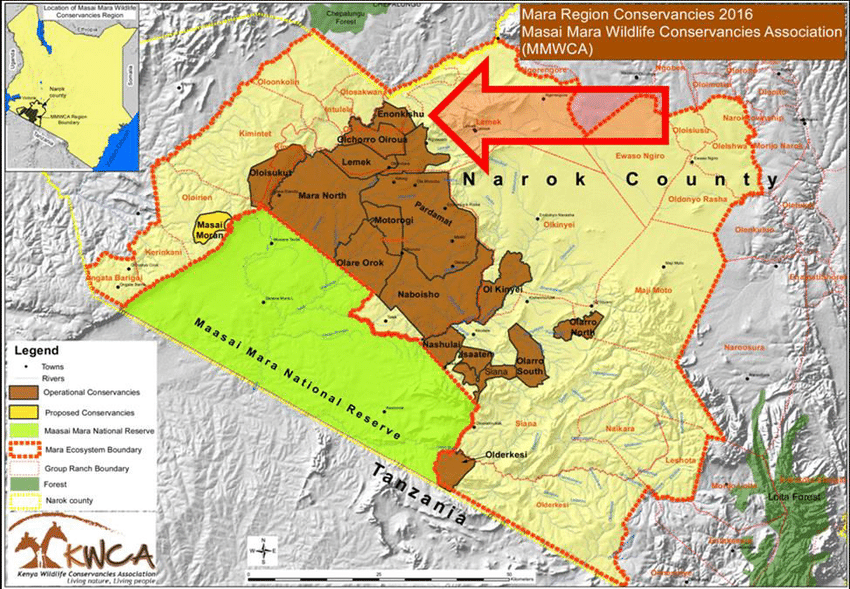

Location and relationship to Masai Mara National Reserve

Enonkishu Conservancy borders the north-western edge of MMNR, forming a critical buffer and dispersal zone between the reserve and the wider pastoral lands of the northern Mara.

Wildlife moves freely across the MMNR–Enonkishu boundary, particularly:

- Large herbivores using seasonal grazing areas

- Predators with wide-ranging territories

- Migratory species linked to the broader Serengeti–Mara system

Why this matters:

Enonkishu absorbs ecological pressure from the reserve by maintaining open, well-managed rangelands, helping stabilise wildlife populations both inside and outside MMNR.

Size, landscape, and habitats

Enonkishu Conservancy covers approximately 6,000–6,500 acres (about 25 km²). While smaller than some neighbouring conservancies, its ecological impact is disproportionally large due to intensive land management and research-led practices.

Key habitat types include:

- Open grassland plains, maintained through planned grazing

- Riverine corridors and seasonal streams, supporting birdlife and predators

- Acacia savannah, providing cover for lions and browsing species

- Regenerating rangeland plots, central to Enonkishu’s conservation model

The conservancy’s landscapes are intentionally managed to improve soil health, grass diversity, and water infiltration.

Foundation, Ownership, governance, and conservancy model

- Founders / origin story (2009): Enonkishu was “born” in 2009 after initial conservancy concept meetings held at the home of Tarquin & Lippa Wood, with early meetings facilitated by Dickson Kaelo.

- Initial landowner coalition: In the 2009 formation phase, ~150 families representing ~24,000 acres participated in early meetings to explore forming a conservancy.

- Early membership attrition (funding gap): After early learning and engagement trips (including support to build buy-in), the project experienced major attrition due to delayed/insufficient funding; by 2012, the impact report notes only 35 families remained committed without funding, and ~18,000 acres were cleared and lost to farming.

- Formal conservancy positioning (MMWCA profile): MMWCA describes Enonkishu as the northernmost point of the Greater Mara ecosystem, covering 5,928 acres, with two tourism partners and 42 landowners (reflecting a later stabilized structure) but latest reports put this figure as high as 6500 acres.

- Name and founding purpose: The name “Enonkishu” (Maa: “healthy cattle”) was selected by community elders and reflects the founding premise: integrating livestock improvement alongside conservation and tourism, rather than treating livestock as incompatible with wildlife.

- Management approach (livestock–wildlife integration): Enonkishu’s model is explicitly based on innovative/holistic grazing planning, including the community decision to keep livestock in one herd (“Kundi Moja” style logic) and contracting an accredited Holistic Management professional to manage grazing plans for a period.

- Governance evolution: The 2020 impact report describes a transition toward more formalized governance rhythms, transparency, and equal stakeholder representation, alongside registration/strengthening of its management plan as an operational roadmap.

- Lease program structure (core economic mechanism): Land remains Maasai-owned, and the conservancy is sustained through land-lease payments funded primarily by tourism and related revenue streams.

- Lease rate and term (published figure): A peer-reviewed working landscape analysis reports Enonkishu land leases are paid at approximately US$25 per acre per year, structured as long-term (15-year) leases, with provisions for members to receive more than the base rate in strong tourism years.

- Implied annual lease payout magnitude (using published rate + MMWCA area): At 5,928 acres × US$25/acre/year, the base lease obligation implied by the published rate is roughly US$148,200 per year (before any “good year” uplift).

- Who pays for leases (tourism partner mechanism): The same analysis states tourism partners pay for the leases that make up the conservancy footprint, linking tourism directly to landowner payouts.

- Kick-start funding for leases (first 3 years): A grant from the African Enterprise Challenge Fund (AECF) is reported to have paid for the first three years of land-lease payments to landowners.

- Tourism revenue streams supporting lease payments (quantified examples): The analysis describes multiple tourism-linked revenue streams feeding conservancy finances, including (i) conservation fees paid by a homeowners development, (ii) a high-end lodge product contributing over US$200,000 per year, and (iii) an education/domestic tourism “hub” contributing ~US$100,000 per year.

- Additional philanthropy supporting leases and operations: Philanthropy is reported as having brought in over US$500,000 since 2018 (via homeowners and lodge guests), helping support lease costs, management costs, and community development projects.

- Landowner numbers (why sources differ): MMWCA lists 42 landowners currently associated with Enonkishu’s conservancy profile, while other project narratives describe earlier or alternative membership counts (e.g., ~32 members) and larger early interest (282 families) before funding constraints reshaped participation. Treat this as evolution over time, not a contradiction.

Regenerative grazing and the “working landscape”

Enonkishu is internationally recognised for pioneering regenerative and holistic grazing systems within the Mara ecosystem.

Core principles include:

- Planned rotational grazing, where livestock are concentrated briefly and moved frequently

- Grass recovery periods that improve root depth and ground cover

- Reduced soil erosion and increased carbon sequestration

This model has demonstrated that livestock and wildlife can coexist while improving ecosystem health—an approach increasingly relevant across African rangelands.

Wildlife and biodiversity

Predators

Enonkishu supports a full predator guild typical of the Mara:

- Lions, often using the conservancy as part of wider territorial ranges

- Leopards, especially near riverine vegetation

- Cheetahs, favouring open plains and low vehicle pressure

- Spotted hyenas and jackals, key scavengers and hunters

Herbivores

Common species include:

- Wildebeest and zebra, especially during seasonal movements

- Giraffe, buffalo, elephant, and multiple antelope species

Migration context

During the Great Wildebeest Migration, Enonkishu functions as a seasonal grazing and dispersal area, particularly early and late in the migration cycle. While major river crossings usually occur deeper inside MMNR, Enonkishu offers quiet migration viewing without crowds.

Research, monitoring, and conservation science

Enonkishu is a major research hub within the Greater Mara, supporting long-term studies on:

- Rangeland regeneration and grassland dynamics

- Predator–prey interactions in mixed-use landscapes

- Carbon sequestration and climate resilience

- Human–wildlife coexistence models

Data generated at Enonkishu informs policy, conservancy management, and scalable conservation practices well beyond the Mara.

Tourism model and visitor experience

Tourism at Enonkishu is deliberately low-volume and carefully integrated into the conservation mission.

Key characteristics:

- Very low vehicle density

- Emphasis on interpretive, educational safaris

- Strong focus on conservation storytelling rather than high-throughput game drives

Visitors typically gain a deeper understanding of how the Mara ecosystem functions, rather than a purely sightings-driven experience.

Activities allowed in Enonkishu Conservancy

Depending on camp arrangements and current conservancy rules, activities may include:

- Day game drives in low-traffic conditions

- Guided walking safaris, focusing on ecology and tracking

- Conservation-focused experiences, such as grazing demonstrations and research interpretation

- Limited night activities where permitted

Activities are designed to reinforce learning, ethics, and low-impact wildlife viewing.

Accommodation within Enonkishu Conservancy

Enonkishu hosts a small number of exclusive, conservation-oriented camps, operating at very low bed numbers.

Accommodation here is best suited for:

- Conservation-minded travelers

- Researchers and students

- Repeat safari guests seeking depth over volume

- Guests interested in land-use and climate solutions

Luxury exists, but always in service of the conservation mission.

Access and logistics

By air

Most visitors fly from Wilson Airport to northern Mara airstrips, followed by a short road transfer into the conservancy.

By road

Road transfers from Nairobi typically take 5–6 hours, depending on route conditions and weather.

Enonkishu Conservancy vs Masai Mara National Reserve

Choose Enonkishu Conservancy if you value:

- Quiet, low-density safari conditions

- Deep conservation and research engagement

- Learning about regenerative grazing and climate resilience

- Ethical, community-led land stewardship

Choose MMNR if you prioritise:

- Iconic Mara River crossings

- Extensive road networks and broad geographic coverage

- A wider range of accommodation options

Best-practice itinerary:

Combine Enonkishu for context, learning, and tranquility, with targeted game drives into MMNR for classic Mara highlights.

Best time to visit

Enonkishu is productive year-round:

- January–March: Strong predator activity, fewer visitors

- July–October: Migration season and peak wildlife numbers

- November–December: Green season with excellent birding and regeneration visibility

Because resident wildlife is strong, quality sightings are not limited to migration months.

Why Enonkishu matters in the Greater Mara

Enonkishu Conservancy is significant because it:

- Demonstrates how conservation and pastoralism can coexist at scale

- Provides a research-backed model for rangeland restoration

- Reduces ecological pressure on MMNR by maintaining healthy buffer landscapes

- Delivers tangible, long-term benefits to Maasai landowners

It is not just a safari destination—it is a living laboratory for the future of African rangelands