The Masai Mara National Reserve is not just a wildlife destination—it is the ecological core of a much larger, living landscape where conservation success depends on community land use, wildlife movement, governance, and tourism economics. Together with surrounding community conservancies and cross-border linkages to the Serengeti National Park, the Mara forms one of the most studied and conservation-critical savannah ecosystems on Earth.

What follows is a structured, end-to-end guide to the key conservation themes shaping the Masai Mara today.

1. Community Conservancies: The Backbone of Modern Mara Conservation

4

Community conservancies are privately and communally owned lands surrounding the National Reserve that are managed for both wildlife conservation and Maasai livelihoods.

How the Conservancy Model Works

- Maasai landowners retain ownership of their land.

- Land is leased collectively to conservation operators.

- Income comes from low-density tourism, not mass visitation.

- Grazing is planned and seasonal, supporting both livestock and wildlife.

Conservation Value

- Expands effective wildlife habitat beyond the reserve boundary.

- Reduces fencing and subdivision by making conservation financially viable.

- Creates direct household income, lowering pressure to sell land.

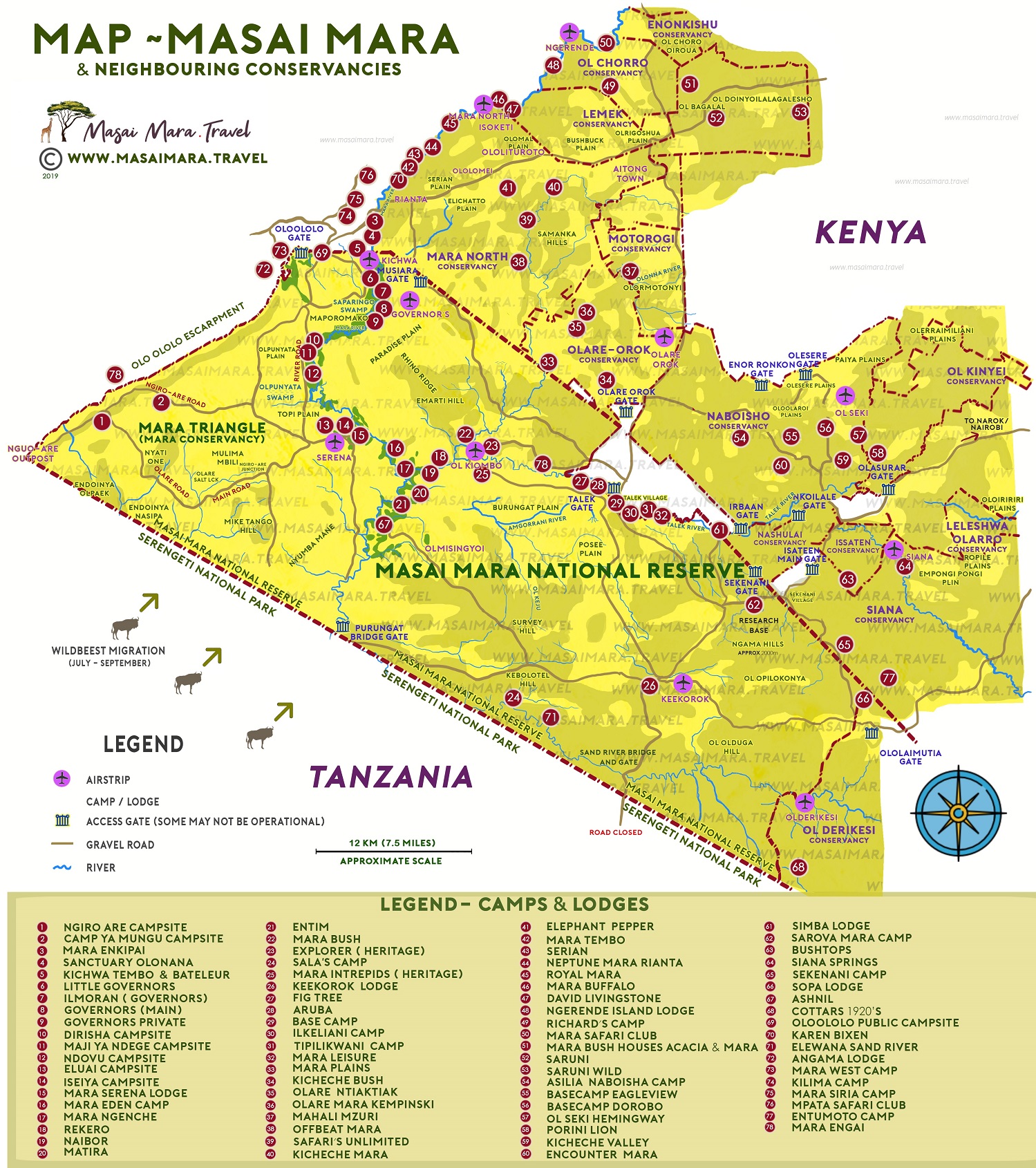

Key examples include Naboisho Conservancy, Olare Motorogi Conservancy, and Mara North Conservancy.

Who Actually Manages Conservation in the Masai Mara?

4

Conservation in the Masai Mara is often misunderstood as being managed by a single authority. In reality, it is governed through a multi-layered management structure, with different institutions responsible for different parts of the ecosystem.

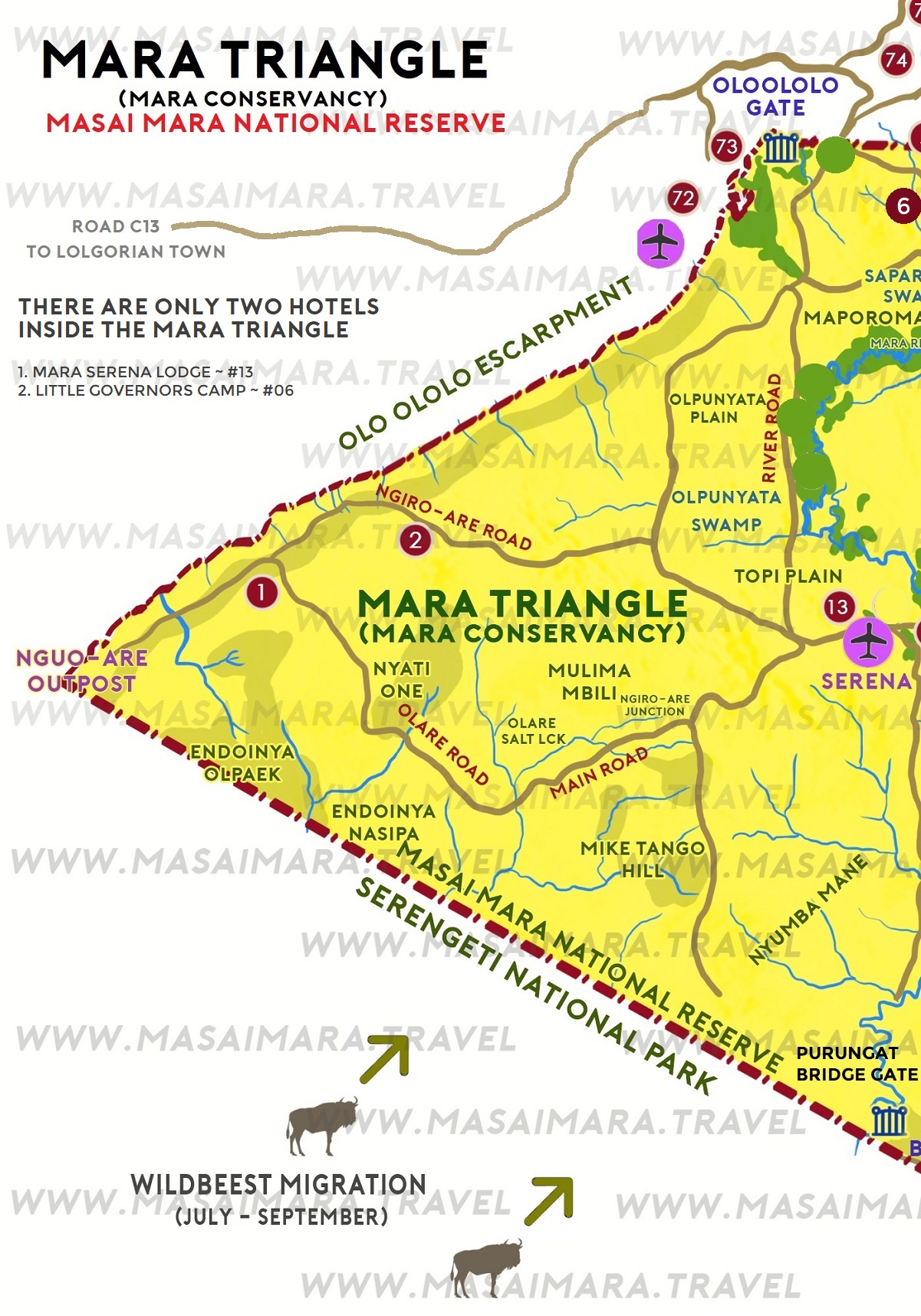

The Masai Mara National Reserve is owned by the Narok County Government. Within it, management is split:

- The eastern and central reserve is overseen directly by the county.

- The Mara Triangle (western section) is managed under contract by the Mara Conservancy, widely regarded for strong governance, transparent finances, and effective law enforcement.

Outside the Reserve boundary, conservation responsibility shifts almost entirely to community conservancies, which are governed by formal agreements between Maasai landowners, conservancy management companies, and tourism partners.

This fragmented governance explains why:

- Enforcement quality varies across zones

- Wildlife densities differ between the Reserve and conservancies

- Conservation outcomes are often strongest where management accountability is clearest

Understanding who manages what is essential to understanding how conservation actually succeeds—or fails—in the Mara.

Why Most Wildlife Lives Outside the Reserve Boundary

One of the most counter-intuitive realities of Masai Mara conservation is that a large proportion of wildlife spends much of its time outside the National Reserve itself.

The Mara is part of the wider Serengeti–Mara ecosystem, where animals move continuously in response to:

- Rainfall variability

- Grass quality

- Water availability

- Breeding and calving cycles

During much of the year, grazers and predators range across community conservancies and unprotected community lands, not just the Reserve.

This makes wildlife corridors and open rangelands more important than formal park boundaries. If land outside the Reserve is subdivided, fenced, or converted to intensive agriculture, the Reserve becomes an ecological island—unable to support large, healthy wildlife populations on its own.

Community conservancies therefore function as:

- Buffer zones that reduce pressure on the Reserve

- Seasonal habitat for migratory and resident species

- The primary defense against ecological isolation

Without them, the Mara’s famous wildlife abundance would decline rapidly, regardless of what happens inside the park gates.

The Mara River: Conservation Beyond Wildlife

4

The Mara River is the ecological spine of the Masai Mara—but its conservation challenges extend far beyond wildlife viewing.

Fed by rainfall and forested catchments in Kenya’s highlands, the river:

- Supplies dry-season water for wildlife, livestock, and people

- Sustains riverine forests and wetlands

- Enables the dramatic wildebeest river crossings

However, the river is under increasing pressure from:

- Deforestation in its headwaters

- Agricultural expansion and irrigation

- Sedimentation from poor land management

- Climate-driven rainfall variability

The Talek River, a key tributary, is particularly vulnerable due to heavy development along its banks.

Effective Mara conservation therefore depends not only on protecting animals, but on catchment-level land use planning, reforestation efforts, and stricter regulation of water abstraction upstream—many kilometers away from the Reserve itself.

Is Fencing Helping or Harming the Masai Mara?

Fencing is one of the most contentious conservation tools in the Mara ecosystem.

Where Fencing Helps

- Protects crops and homesteads from elephants

- Reduces night-time livestock losses

- Increases community safety and tolerance for wildlife

Where Fencing Harms

- Blocks ancient migration routes

- Fragments habitat and isolates populations

- Concentrates wildlife pressure in smaller areas

- Increases conflict at fence edges

In the Mara, poorly planned fencing is widely recognized as a long-term ecological risk, particularly in known wildlife corridors. As a result, conservation planners increasingly favor corridor protection, negotiated grazing agreements, and targeted deterrents over continuous fencing.

The goal is not zero conflict—but coexistence without ecological collapse.

2. Wildlife Corridors: Keeping the Mara Ecologically Connected

4

Wildlife corridors are movement pathways that allow animals to access grazing, water, breeding areas, and seasonal ranges.

Why Corridors Matter

- The Great Wildebeest Migration depends on unrestricted movement.

- Predators require large territories to remain genetically viable.

- Seasonal rainfall variability makes mobility essential for survival.

Current Threats

- Agricultural expansion and permanent settlements.

- Road development and fencing.

- Unplanned tourism infrastructure near rivers.

Corridors linking the Mara to the Serengeti—and between the Reserve and conservancies—are among the highest conservation priorities in East Africa.

3. Human–Wildlife Conflict: Living with Wildlife at Scale

4

As wildlife populations recover and human populations grow, conflict becomes inevitable—but manageable.

Common Conflict Types

- Livestock predation by lions, leopards, and hyenas.

- Crop damage by elephants and buffalo.

- Risk to human safety near water points and grazing areas.

Mitigation Strategies

- Predator-proof bomas (reinforced livestock enclosures).

- Community wildlife scouts and rapid response teams.

- Compensation and conservation incentive schemes.

- Land-use zoning that separates high-risk areas.

Effective conflict mitigation is central to long-term tolerance for wildlife.

4. Anti-Poaching: Security as Conservation Infrastructure

4

Poaching in the Mara has declined significantly, but constant vigilance remains essential.

Modern Anti-Poaching Approaches

- Professionally trained ranger units.

- Aerial surveillance and real-time radio networks.

- Intelligence-led patrol deployment.

- Collaboration between county authorities, conservancies, and communities.

The Mara Conservancy, which manages the Mara Triangle, is widely regarded for its effective enforcement and transparent governance.

5. Rhino Conservation: Small Numbers, High Protection

4

Rhinos are among the most intensively protected species in the Mara ecosystem.

Key Characteristics

- Mostly black rhinos, with a small number of white rhinos.

- Concentrated in secure zones with armed protection.

- Intensive monitoring, including individual identification.

Conservation Significance

- Rhinos act as a barometer of security effectiveness.

- Their survival reflects successful anti-poaching systems.

- Even small populations contribute to national metapopulation recovery.

6. Predator Conservation: The Mara as a Global Stronghold

4

The Masai Mara supports one of Africa’s densest large-carnivore assemblages.

Conservation Challenges

- Retaliatory killing linked to livestock loss.

- Habitat fragmentation reducing hunting ranges.

- Tourism pressure at sensitive sightings.

Conservation Responses

- Long-term research and monitoring of prides and coalitions.

- Community compensation programs.

- Tourism codes of conduct to reduce disturbance.

Healthy predator populations indicate ecosystem integrity, not imbalance.

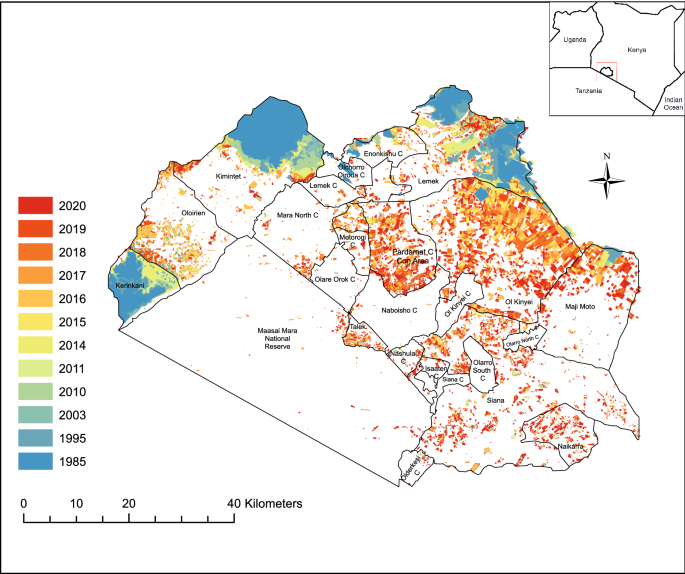

7. Land Fragmentation: The Single Greatest Long-Term Risk

4

Subdivision and fencing of former communal lands pose the largest structural threat to the Mara.

Impacts of Fragmentation

- Loss of migration routes.

- Increased human–wildlife conflict.

- Genetic isolation of wildlife populations.

- Reduced resilience to drought and climate change.

Why Conservancies Matter Here

Conservancies directly counter fragmentation by keeping land open, economically productive, and ecologically functional.

8. Sustainable Tourism: Financing Conservation Without Destroying It

4

Tourism funds conservation—but only when carefully managed.

Principles of Sustainable Tourism in the Mara

- Low vehicle densities, especially in conservancies.

- Revenue sharing with local landowners.

- Strict guiding and wildlife viewing standards.

- Investment in conservation and community services.

Conservation Trade-Offs

High-volume tourism risks degrading habitats, while low-density, high-value tourism has proven far more compatible with conservation outcomes.

How Your Choice of Camp Directly Affects Conservation

4

In the Masai Mara, where you stay matters as much as what you see.

When you stay in a community conservancy:

- Your bed-night fees fund land leases that keep land open and unfenced

- Conservation levies pay ranger salaries, vehicles, and patrols

- Tourism income replaces pressure to subdivide land

- Wildlife gains secure habitat outside the Reserve

By contrast, Reserve-only stays primarily support park operations but do not directly prevent land fragmentation on surrounding community lands.

Questions worth asking before booking:

- Do my fees include a conservancy land lease?

- How many vehicles are allowed per sighting?

- How does this camp support community livelihoods?

- What limits are in place to reduce environmental impact?

In practical terms, choosing a conservancy stay is one of the strongest conservation actions a visitor can take.

Why Climate Change Makes Conservancies Even More Important

Climate change is already reshaping the Mara:

- Rainfall is more erratic

- Dry spells are longer

- Migration timing is shifting

- Rivers face greater dry-season stress

In a changing climate, large, connected landscapes are more resilient than small, isolated protected areas.

Community conservancies increase resilience by:

- Preserving movement options during drought

- Spreading grazing pressure across wider areas

- Allowing adaptive land-use planning

- Reducing dependence on a single tourism or rainfall pattern

As climate variability increases, the future of the Masai Mara will depend less on fixed boundaries and more on flexible, community-led conservation at landscape scale.

The Bigger Picture: Why Masai Mara Conservation Matters Globally

The Masai Mara is not conserved because it is famous—it is famous because it still functions. Its open grasslands, intact predator guild, and seasonal migrations represent a version of African savannah ecology that has disappeared in many other regions.