Anti-poaching in the Greater Mara is not just about “armed rangers chasing poachers.” It’s a full wildlife-crime system—prevention, intelligence, patrol coverage, rapid response, evidence handling, and prosecutions—operating across a huge, porous landscape where wildlife move freely between the reserve, conservancies, and community lands. In the Mara, the most persistent pressure is often snaring for bushmeat (a high-volume, low-visibility threat), with episodic spikes in high-value trafficking risks (especially where cross-border routes and organized networks are active).

1) What counts as “wildlife crime” in the Mara context

Wildlife crime in the Mara typically clusters into:

- Bushmeat poaching (snaring): wire snares set along game paths; indiscriminate by design—anything from zebra to lion can be injured or killed.

- Trophy poaching / high-value species targeting: less frequent than snaring in many periods, but highest risk for iconic species.

- Illegal grazing, encroachment, and resource extraction: can degrade habitat and create cover/routes for offenders, and can also become enforcement flashpoints.

- Trafficking and “micro-wildlife” trade: Kenya has documented cases of illegal trade expanding beyond the classic ivory/rhino-horn narrative into other taxa (a broader wildlife-crime economy).

Why this matters for conservation: snaring can quietly remove large numbers of animals and create long-term injury burdens; targeted trafficking can destabilize small, high-value populations quickly.

2) Why the Mara is uniquely exposed

Key vulnerability drivers:

- A vast, open ecosystem with multiple entry points (reserve edges, conservancy boundaries, riverine corridors).

- Cross-border pressure dynamics: the Mara sits in a wider Serengeti–Mara system; security issues can be influenced by transboundary movement and enforcement coordination. The MMNR management plan explicitly notes joint operations and cooperation with Tanzanian authorities in response to poachers entering from Tanzania.

- Economic incentives + local protein markets: demand for bushmeat can increase snaring pressure (and it’s hard to detect because it doesn’t require gunshots or vehicles).

3) The anti-poaching actors you need to understand

Anti-poaching in the Mara is a multi-actor governance environment:

- Kenya Wildlife Service: national agency with enforcement mandate and public reporting channels (including a toll-free line and WhatsApp contact).

- Mara Conservancy: manages the Mara Triangle and publicly documents its security operations, including anti-poaching and de-snaring patrols and canine capability.

- Narok County ecosystem governance: the reserve is county-managed, so coordination among reserve management, conservancies, and national agencies is operationally important (especially for joint patrols, intelligence-sharing, and prosecutions).

- Conservancy ranger teams & partners: many conservancies run professional ranger units, often supported by donor funding, tourism levies, and partner organizations.

Practical implication for visitors and operators: the best-protected zones are typically those with consistent funding, strong governance, and integrated patrol + intelligence systems—not just “more rangers.”

4) The modern anti-poaching model in the Mara

Effective anti-poaching in the Greater Mara typically uses a layered model:

A) Prevention and deterrence

- Visible patrol presence in high-risk corridors and near known entry routes

- Community deterrence (local intelligence, “eyes on the ground,” rapid reporting)

- Tourism compliance (vehicle discipline reduces cover for offenders and protects evidence scenes)

B) Detection and intelligence

- De-snaring sweeps (removing snares before they kill; mapping snare hotspots)

- Intelligence-led patrol tasking (where patrols are deployed based on recent incidents, informant reporting, and risk mapping)

- Canine units where relevant (tracking / detection functions are explicitly highlighted by Mara Triangle security operations).

C) Rapid response and interdiction

- Time matters: responses are most effective when teams can reach an incident quickly (fresh tracks, intact scenes, recoverable evidence).

D) Evidence, legal process, and prosecution

Kenya’s wildlife framework includes specific offences and penalties under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (Kenya Law publishes the consolidated text).

Why this matters: successful anti-poaching is not only arrests—it’s case quality (evidence chain, charge sheets, court outcomes).

5) What “good anti-poaching” looks like on the ground

If you’re explaining this on MasaiMara.ke for a general reader, anchor on observable, credible signals:

- De-snaring is routine, not occasional (snare removal is one of the clearest operational indicators of bushmeat-poaching pressure and response).

- Patrols are continuous and structured, not ad-hoc (coverage plans, patrol logs, incident reporting).

- Transboundary coordination exists where cross-border threats are material.

- Community engagement is operational (not just “awareness”): reporting networks, conflict reduction, and incentives aligned to protect wildlife.

- Transparent governance and resourcing (stable funding—often via conservancy fees/tourism—supports consistent enforcement).

6) Wildlife-crime “hotspots” in the Mara

You’ll generally see higher snaring risk in:

- Riverine corridors and bushy edges where wildlife funnels through predictable paths

- Boundary zones where offenders can enter/exit quickly

- Areas with livestock–wildlife interface, where both bushmeat snaring and retaliatory actions can overlap

For higher-value trafficking risks, vulnerability rises where:

- Access routes allow discreet movement out of the ecosystem

- Enforcement gaps exist (nighttime, low patrol density, poor radio coverage)

7) What visitors, guides, and camps can do (without endangering anyone)

This is a high-value section for MasaiMara.ke because it turns concern into safe, practical action:

Promote responsible tourism norms (vehicle discipline reduces stress on wildlife and preserves the quality of ranger evidence when incidents occur).

Report suspicious activity—don’t investigate. Use official channels (Kenya Wildlife Service provides a toll-free and WhatsApp contact).

Don’t share real-time locations of sensitive species publicly (especially rhino or den sites).

Respect scene integrity: if you encounter a carcass/snare, keep distance and report; avoid driving over tracks or disturbing the area.

Choose stays and operators that fund conservation: conservancy fees and well-governed management bodies help pay for patrol coverage and equipment.

Poaching Statistics in the Masai Mara

Poaching in the Masai Mara is a persistent threat, particularly for species such as elephants and rhinos. Here are some key statistics that highlight the severity of the issue:

- Elephants: According to the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), elephant populations in Kenya have declined by over 50% in the past three decades, with poaching being the primary cause. In the Masai Mara, elephant poaching peaked in 2012, with nearly 100 elephants killed in a single year.

- Rhinos: The black rhino population in Kenya was nearly wiped out in the 1970s and 1980s due to poaching. Today, only about 35 black rhinos remain in the Masai Mara. The region’s rhinos are critically endangered, and poaching remains a significant threat to their survival.

- Bushmeat Poaching: Studies indicate that bushmeat poaching is the most prevalent form of poaching in the Masai Mara. A 2020 report by the African Wildlife Foundation estimated that over 50,000 animals are killed annually in Kenya for bushmeat consumption, with a significant portion occurring in the Masai Mara region.

- Snares: Anti-poaching patrols in the Masai Mara remove thousands of snares annually. For example, in 2021, the Mara Elephant Project reported removing over 3,000 snares in the Greater Mara ecosystem.

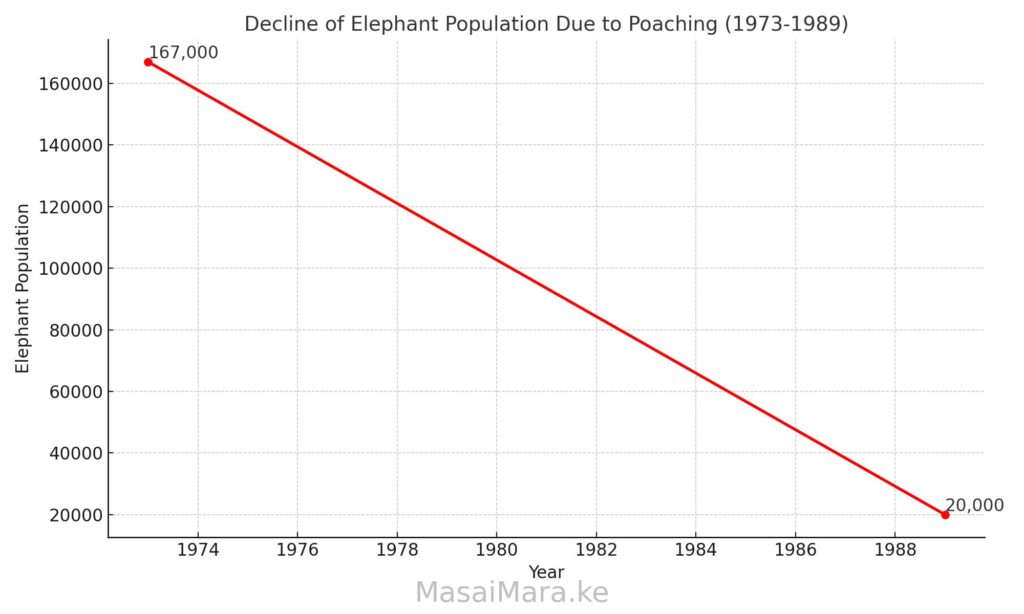

As outlined in the National Elephant Action Plan, Kenya’s elephant population experienced a significant decline, plummeting from 167,000 individuals in 1973 to just 20,000 by 1989, primarily driven by rampant ivory poaching.

Types of Poaching in the Masai Mara

Poaching in the Masai Mara can be categorized into several types, each driven by different motivations and impacting various species:

1. Trophy Poaching

Trophy poaching involves the killing of animals for their valuable parts, such as elephant tusks and rhino horns. This type of poaching is driven by the illegal wildlife trade, which is fueled by demand from countries in Asia and the Middle East.

Impact:

- Significant reduction in elephant and rhino populations

- Disruption of ecosystems due to the loss of keystone species

2. Bushmeat Poaching

Bushmeat poaching involves the illegal hunting of wildlife for meat. It is often driven by poverty and lack of alternative livelihoods for local communities.

Impact:

- Depletion of wildlife populations, including antelopes, zebras, and wildebeests

- Increased risk of zoonotic diseases spreading to humans

3. Snaring and Trapping

Snaring is a common method used by poachers to capture animals. Snares are inexpensive and easy to set up but cause immense suffering to wildlife.

Impact:

- Non-target species, including lions and cheetahs, often fall victim to snares

- Injuries and slow, painful deaths for trapped animals

4. Cultural Poaching

In some cases, poaching is driven by cultural practices. For example, young Maasai warriors traditionally killed lions as a rite of passage. While this practice has largely diminished due to education and conservation efforts, it still occurs in some remote areas.

Impact:

- Targeted reduction in predator populations

- Increased human-wildlife conflict as lions retaliate against livestock attacks

Drivers of Poaching in the Masai Mara

Several factors contribute to the persistence of poaching in the Masai Mara:

1. Economic Pressures

Many local communities around the Masai Mara live in poverty and lack access to formal employment. Poaching provides a source of income through the sale of bushmeat or participation in illegal wildlife trade networks.

2. Demand for Wildlife Products

Global demand for ivory, rhino horn, and other wildlife products remains high, particularly in countries like China and Vietnam. These products are often used in traditional medicine or as status symbols.

3. Human-Wildlife Conflict

Human-wildlife conflict is a significant driver of poaching. When predators kill livestock, local communities may retaliate by killing the offending animal.

4. Weak Law Enforcement

While Kenya has strong anti-poaching laws, enforcement in remote areas like the Masai Mara can be challenging. Poachers often operate at night, making it difficult for rangers to catch them.

Impact of Poaching on the Masai Mara Ecosystem

Poaching has far-reaching consequences on the Masai Mara ecosystem:

- Decline in Wildlife Populations: Poaching leads to population declines, particularly in large mammals such as elephants, rhinos, and lions.

- Disruption of Ecosystem Balance: The loss of key species can disrupt predator-prey dynamics and lead to overgrazing by herbivores.

- Economic Loss: Poaching negatively impacts tourism, which is a major source of income for Kenya. Reduced wildlife sightings can deter tourists from visiting the Masai Mara.

Anti-Poaching Efforts in the Masai Mara

Several organizations and initiatives are working to combat poaching in the Masai Mara:

1. Mara Elephant Project (MEP)

MEP focuses on protecting elephants in the Greater Mara ecosystem through anti-poaching patrols, community engagement, and the use of technology such as GPS tracking collars.

2. Narok County Government

The Narok County Government manages the Masai Mara National Reserve and works to enforce anti-poaching laws within the reserve.

3. Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS)

KWS is responsible for wildlife conservation and management in Kenya. They conduct anti-poaching operations and work with local communities to promote conservation.

4. Conservancies

Community-owned conservancies surrounding the Masai Mara have proven effective in reducing poaching by providing alternative livelihoods for local communities and promoting sustainable tourism.

Technological Innovations in Anti-Poaching

Recent advancements in technology are helping to improve anti-poaching efforts in the Masai Mara:

- Drone Surveillance: Drones are used to monitor large areas of the reserve and detect poaching activities.

- GPS Tracking: Animals are fitted with GPS collars to track their movements and alert rangers if they move into high-risk areas.

- Camera Traps: Hidden cameras are used to capture images of poachers and wildlife in remote areas.

How Tourists Can Help Combat Poaching

Tourists visiting the Masai Mara can play a role in combating poaching by:

- Choosing Ethical Tour Operators: Support operators that promote responsible tourism and work with local communities.

- Reporting Suspicious Activities: If you see anything suspicious during your safari, report it to park authorities.

- Supporting Conservation Organizations: Donate to organizations working to protect wildlife in the Masai Mara.

Conclusion

Poaching remains one of the biggest threats to the Masai Mara’s wildlife. While significant progress has been made in combating poaching, ongoing efforts are needed to address the root causes and protect the region’s unique biodiversity. By supporting anti-poaching initiatives and promoting sustainable tourism, we can help ensure that future generations continue to experience the magic of the Masai Mara.

Related: